The European Conservatives and Reformists in the European Parliament: A Big Tent with a Brown Lining

by Ellen Rivera

IERES Occasional Papers, no. 23, May 2024 “Transnational History of the Far Right” Series

Photo: Image by John Chrobak.

The contents of articles published are the sole responsibility of the author(s). The Institute for European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies, including its staff and faculty, is not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement expressed in the published papers. Articles do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute for European, Russia, and Eurasian Studies or any members of its projects.

©IERES 2024

This is the first of two articles enquiring into the European Conservatives and Reformists Group and Party and their extended apparatus (the ECR) in the European Parliament and beyond. Part one gives a broad overview of the history and structure of the ECR and an outlook on its expected performance in the upcoming June 2024 election. Part two dives deeper into the ECR’s ideology and its radicalization process, with a special focus on its think tank New Direction.

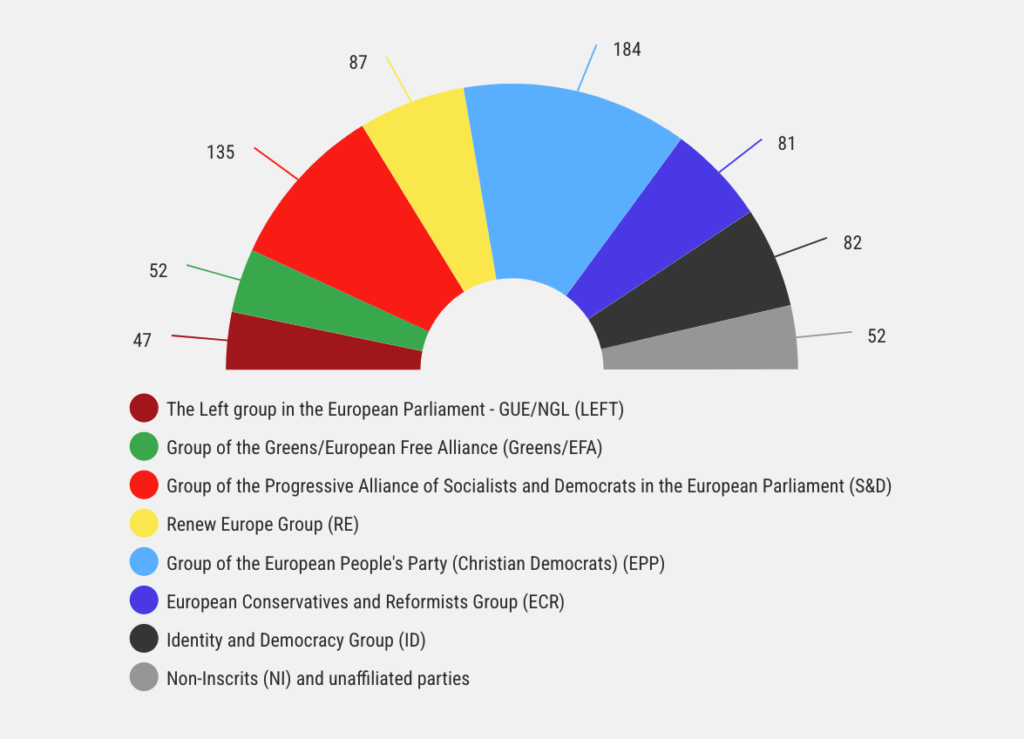

Experts foresee a sharp right turn looming following the June 2024 European election, with the right-wing to far-right faction in the European Parliament expected to get hold of almost a quarter of the seats.[1] For the first time, a center-right to far-right coalition could emerge in the EU Parliament with enough votes to bring about a reactionary turn on a broad scale of issues, such as climate, immigration, and gender policies, and may further erode European cohesion—unbeknownst to most of the European public, which keeps little track of Brussels politics. As right-wing to far-right parties across Europe are poised to gain power, their growth is manifested most dangerously at the top of the European Union, where they are clustered in European political groups and parties which reflect similar ideologies. Inside the European Parliament, the right is represented by two political groups, the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR: the subject of this article), and the even more extreme Identity and Democracy (ID).

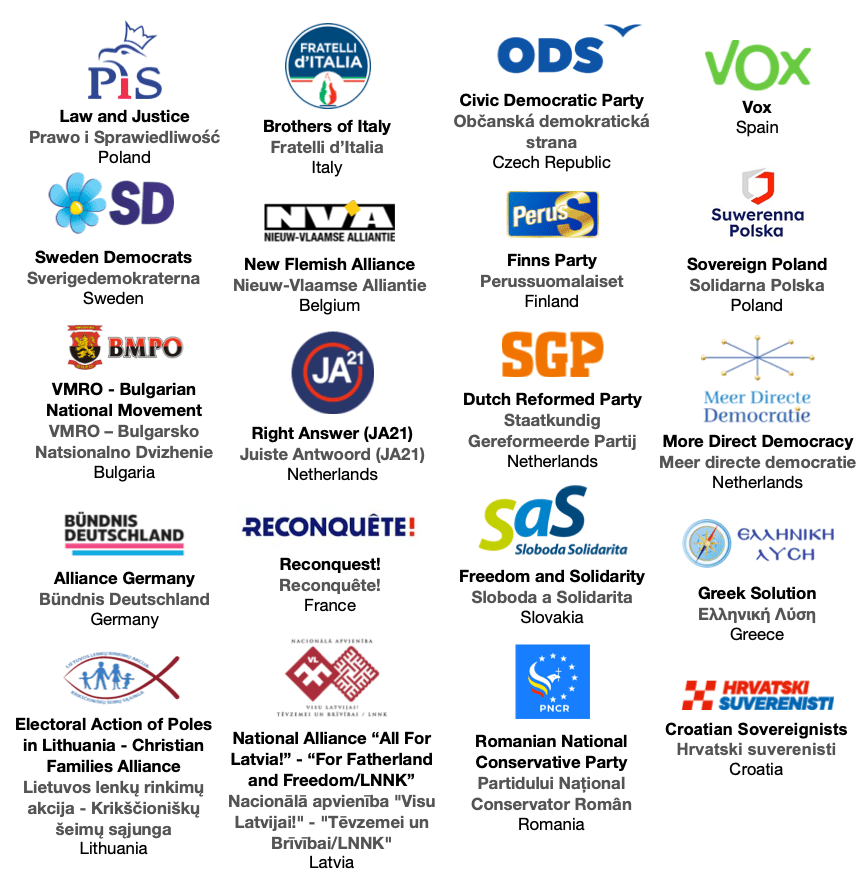

The ECR Group, which may grow by 15 to 20% following the upcoming EU election, is part of a larger apparatus that also includes the ECR Party and affiliated organizations, such as the think tank New Direction (altogether called the ECR hereafter). To explain the ECR’s recent successes, this article provides an overview of its history and structure, with a particular focus on the ECR Group, concluding with an outlook on the upcoming EU election. At present, the ECR Group has 20 member parties, and its members of the European Parliament (MEPs) hold 68 out of 705 seats, a number that may rise to more than 80 following the 2024 EU election.[2]

The ECR serves as a big tent for largely right-wing to far-right parties, including parties with a neofascist, and even neo-Nazi, heritage. By presenting itself as center-right and merely conservative, the ECR aims to provide a respectable cover for its ever more extreme constituents.[3] While ECR was long under the sway of the UK Conservative Party, today, it is dominated by right-wing to far-right parties, such as Law and Justice (Poland), Vox (Spain), Brothers of Italy, and the Sweden Democrats. A certain British influence is still exerted through some of the ECR-affiliated organizations, such as New Direction, or the ECR Party representation in the Council of Europe. Classified as “soft Eurosceptic,” the ECR does not intend to dissolve but rather to take over the European Union.

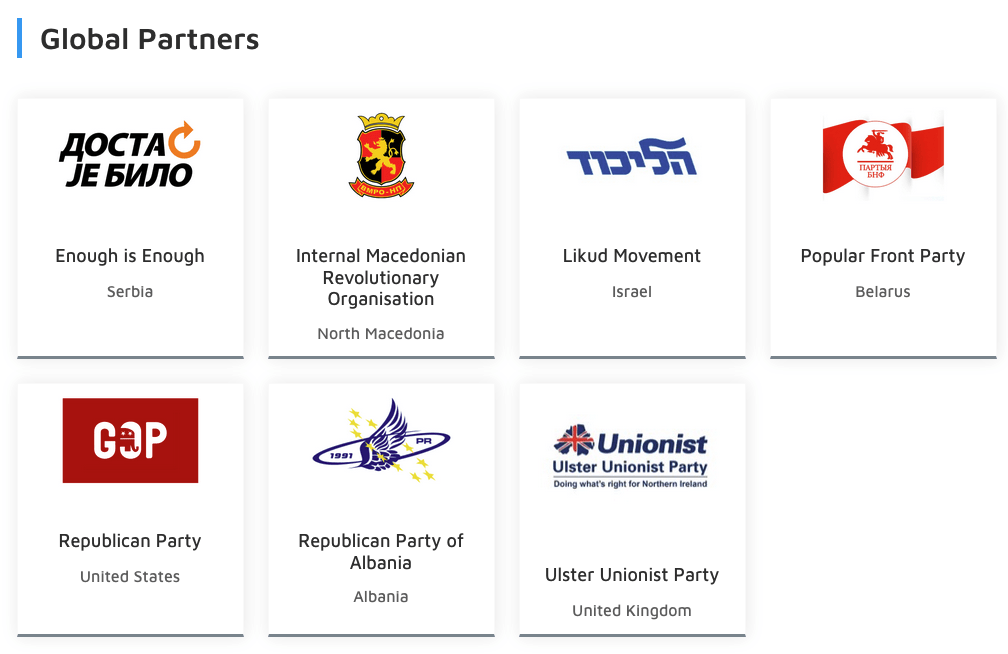

The ECR is largely a collection of staunch pro-NATO and anti-Russian national parties—a feature that has become more marked following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and distinguishing it from its competitor, Identity and Democracy, which mostly gathers national parties sympathizing with Russia under Putin, while some even oppose NATO. Internationally, the ECR’s allies include the US Republican Party and the Israeli Likud party, as well as a long list of right-wing partner organizations and lobbying groups.

History

As the ECR’s history has been detailed at length by Martin Steven and others, this article provides only a broad overview of the most important developments within the ECR, with a focus on elucidating the ECR’s radicalization process from a largely center-right to right-wing, to a right-wing to far-right political force.[4]

While the ECR Group and Party were founded only fairly recently, in 2009, the history of their precursors goes back to 1973, when the European Community enlarged for the first time, to include the United Kingdom, Denmark, and Ireland. Subsequently, the British Conservative Party and the Danish Conservative People’s Party spearheaded the formation of a new parliamentary group, the European Conservative Group (1973–1979), which was dominated by the Tories—the earliest precursor of today’s ECR. During the Margaret Thatcher era, the group rebranded to European Democrats (ED) (1979–1992), which existed until the signing of the Maastricht Treaty, which concluded the foundation of the European Union.

In 1992, during the tenure of John Major as Britain’s prime minister, ED ceased operating as an independent group due to a lack of support. That year, ED’s members joined the more moderate Christian-democratic European People’s Party as a subgroup, to form the European People’s Party–European Democrats (EPP-ED)—a semi-merger that lasted 17 years (1992–2009).[5] This “marriage of convenience” was always on a weak footing, particularly due to the Tories’ unwillingness to share power with the German Christian Democrats, the dominant force within EPP.[6] Nonetheless, the contacts formed back then contributed to the ECR’s continued collaboration with the EPP to the present day.

The merger between EPP and ED started to crumble around 2005 following a leadership change in the British Conservative Party in favor of Prime Minister David Cameron. To satisfy the demands of the right wing inside his own party, in 2006 Cameron promised that the Tories would leave EPP-DE and start a new group, blaming EPP-ED for being too federalist and opposing stronger European integration.[7] However, its launch was delayed until the following EU election in 2009, all the while the Conservative Party remained attached to EPP-ED. In the interim period, from July 2006 to October 2009, a pan-European alliance called the Movement for European Reform (MER) was established to prepare the launch of the new group, which operated outside of the EU Parliament.[8]

Relations further deteriorated when the EPP voiced its opposition to the UK holding a referendum on the ratification of the Treaty of Lisbon, something for which the Tories had campaigned.[9] In March 2009, Cameron announced that the Conservative Party would leave EPP and create a new group following the EU election. That month, a constitutive text known as the Prague Declaration was published, outlining the ideological cornerstones of the future group.[10]

The 10-point-program starts out with a string of classic neoliberal demands: free trade and enterprise; minimizing regulations and taxation; and individual freedoms. These are followed by a set of talking points near and dear to the right: a focus on the family as the “bedrock of society”; more national sovereignty for European Union member states (a policy also referred to as “subsidiarity”); and curbing and controlling immigration. Point six is a commitment to strengthening relations with NATO and with the US.

After the European election in June 2009, the new group and party were launched, initially called the Alliance of European Conservatives and Reformists (AECR)—named in reference to the 1970s group. The first official list of the AECR Group included 55 members, notably from the British Conservatives, the Polish Law and Justice (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość: PiS) party, and the Czech Civic Democratic Party (Občanská demokratická strana: ODS).[11] Later in 2009, the AECR also created a think tank, New Direction, whose founding patroness was Margaret Thatcher, with former high-ranking military intelligence officer Geoffrey van Orden as first head.

In its early years, the new group and party faced considerable friction over the imposing role of the Tories, who wanted to take the top leadership spots.[12] And although some concessions were made, the British delegation managed to secure a dominant influence. One of the early leadership debacles occurred when the group’s chairman, the Polish PiS MEP Michał Kamiński left his party in November 2010, stating that it had been usurped by the far right. Thereupon, he was frozen out on the initiative of the AECR’s other PiS MEPs, and in February 2011, he finally stepped down, giving way to a number of leadership changes.[13]

Although the founding members of the AECR were largely center-right to right-wing, with a neoliberal and anti-federalist (but not secessionist) outlook, only at the very outset were there some disagreements over whether to include staunchly anti-immigrant and ultranationalist parties.[14] Such limitations started to crumble already shortly after the AECR’s inception—for example, when in late March 2011, David Cameron tried unsuccessfully to win over the New Flemish Alliance (Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie: N-VA) to join the group, a Belgian nationalist and secessionist party rallying for the formation of an independent Flemish state.[15] In 2014, the party joined after all. Meanwhile, member parties, such as PiS, went through a steady radicalization process.

The general rise of the right in Europe reverberated in the 2014 European elections, which were held in May 2014, and marked the end of the AECR’s brief demarcation from the more extreme right.[16] Following the elections, the AECR group accepted applications from the New Flemish Alliance, the Danish People’s Party (Dansk Folkeparti: DF), the Finns Party (Perussuomalaiset: PS), and the Alternative for Germany (Alternative für Deutschland: AfD). With their accession, the AECR became the third-biggest group in the European Parliament, and thus considerably increased its leverage.[17]

The AECR’s admission of extreme right-wing parties was heavily criticized, not least because the Danish and Finnish delegations included MEPs who had been convicted of racist and Islamophobic statements.[18] The leading candidate of the Danish People’s Party, Morten Messerschmidt, was convicted in 2002 for claiming that multiethnic societies were a breeding ground for rape and violence.[19] And Finns Party MEP Jussi Halla-aho had been sentenced in 2012 for inciting racial hatred after publishing a blog post that, among other things, purported Islam reveres pedophilia.[20] Notwithstanding, the Conservative Party member Syed Kamall, at the time Leader of the Conservatives in the European Parliament (a now defunct post), himself a practicing Muslim, defended the new members.[21]

Despite the open door policy for extreme right-wing parties, the AECR started a procedure to exclude its two Alternative for Germany MEPs in March 2016, ostensibly due to the party’s links with the far-right Freedom Party of Austria (Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs: FPÖ), and its extreme anti-immigration rhetoric. The motion followed a high-level meeting of far-right party leaders in Düsseldorf in February 2016, intended to form a German-Austrian “Blue Alliance.”[22] There, the pro-Russian tendencies of AfD and FPÖ were on full display, which angered the staunchly anti-Russian PiS MEPs in the AECR.[23] Already back then, a split within the right between pro- and anti-Russian camps was apparent, with an anti-Russian and pro-NATO stance increasingly becoming the norm within the AECR.

In October 2016, a few months after the Brexit referendum, both the AECR group and the party changed their names from the Alliance of European Conservatives and Reformists to the Alliance of Conservatives and Reformists in Europe (ACRE). During the eighth EU legislature, ACRE became the focus of financial investigations and had to repay EU funds to the tune of over half a million euros. ACRE had apparently misused funds to host events that were “of limited relevance or benefit to the EU.”[24] These included a three-day event in a Miami Beach resort with a predominantly American audience, and a post-Brexit trade conference in Kampala, Uganda, which consisted largely of British and African delegates.

After Brexit, a further shift to the right ensued within ACRE, which can be explained by several factors: with the UK Conservative Party’s dominating force ceasing within ACRE, the power vacuum was filled by member parties further to the right. At the same time, there was a need to make up for the loss of British MEPs. A pool of potential new partners opened up with the impending collapse of the secessionist Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy (EFDD) group and the Alliance for Direct Democracy in Europe (ADDE) party, led by UK Independence Party cofounder Nigel Farage, which necessitated national member parties to choose other parliamentary allies. As such, the far-right Sweden Democrats (Sverigedemokraterna: SD) left EFDD and moved to the ACRE group in July 2018—a party with neo-Nazi roots.[25]

Following the 2019 European election, the Alliance of Conservatives and Reformists in Europe rebranded once more as European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR, 2019–present). During the current EU legislature (2019–2024), even more extreme right-wing parties joined the ECR.[26] These notably included Brothers of Italy (Fratelli d’Italia: FdI) and the Spanish Vox party. At the same time, it marked the end of British representation in the European Parliament, when on January 31, 2020 the UK’s withdrawal from the European Union was finalized. Following the election, the ECR also experienced some minor outflow due to the formation of a new right-wing to far-right faction in the European Parliament, the rivaling Identity & Democracy (ID) party and group, spearheaded by Italy’s League and the Alternative for Germany.[27]Subsequently, two ECR member parties, the Danish People’s Party and the Finns Party, quit ECR and joined ID.

Although the ECR was always predominantly pro-NATO, the war in Ukraine has made a pro-NATO and anti-Russian stance a decisive differentiating factor vis-à-vis ID. In February 2023, ECR group Chairman Ryszard Legutko of the Polish PiS party stated that the group shall stand by Ukraine until Russia is defeated and beyond.[28] Following the 2023 Finnish parliamentary election, the Finns Party, previously attached to ID, rejoined the ECR, citing their change in policy to endorse Finnish NATO membership as the reason for the move.[29]

While the ECR is generally considered a bit less extreme than ID, both the ECR and ID align on many other issues such as immigration, environment, and gender policies, and have come together on single issues put to vote in the European Parliament. In the Council of Europe, their respective Europarties have even formed a joint platform, the European Conservatives Group and Democratic Alliance.

Structure

The ECR apparatus consists of several interwoven structures: the European political group (ECR Group) and the European political party (ECR Party). Affiliated with the ECR Party are a think tank, New Direction; and an institutionally separate youth wing, the European Young Conservatives.

In structural terms, the political group constitutes the formal representation of the Europarty in the European Parliament, although both entities have different functions and limitations under EU law.[30] Inside the European Parliament, affiliation with a political group takes precedence, whereby members of each group sit together in a designated area in the parliamentary ranks. The seating order in the European Parliament corresponds to the political leaning of each group. As such, the ECR group sits between the center-right EPP and the right-wing to far-right ID.

A further difference between party and group concerns political campaigning: only Europarties are allowed to fund or organize political campaigns, whereas this is strictly prohibited for groups. And in contrast to groups, Europarties can also have member parties with no elected members in the European Parliament. The overlap of member parties in European groups and parties is usually rather large (in the case of the ECR, approximately two-thirds), although the Europarty has fewer member parties than the group.

The ECR Group

The ECR Group (ECRG) is the fifth-largest of the seven groups in the European Parliament, and its 68 MEPs occupy 9.6% of its seats.[31] In the 2019 European Parliament election, the ECRG got hold of 62 seats; however, after the final Brexit deal in 2020, it received a few more when a portion of the UK’s seats were redistributed.[32] The ECR Group currently includes MEPs from 20 national member parties, of which many are members of the ECR Party as well. But it also includes national parties that belong to other Europarties, such as the European Christian Political Movement and the European Free Alliance, as well as independent MEPs.

While some of the larger parties, such as the Polish PiS party, or the Czech ODS, have been there from the start, in particular the composition of the small parties has changed over the years. The PiS party delegation, with 25 seats, is by far the largest, followed by Brothers of Italy (10 seats), Vox (4 seats), ODS (4 seats), the Sweden Democrats (3 seats); the New Flemish Alliance (3 seats), the Finns Party (2 seats), VMRO—Bulgarian National Movement (2 seats), and Sovereign Poland (2 seats). The remaining parties only sent one MEP each: Alliance Germany, the Dutch Reformed Party, the Electoral Action of Poles in Lithuania, Freedom and Solidarity (Slovakia), Greek Solution, JA21 (Netherlands), National Alliance (Latvia), the Romanian National Conservative Party, the Croatian Sovereignists, More Direct Democracy (Netherlands), and Reconquest (France).

Currently, the ECRG is co-chaired by Ryszard Legutko of the PiS party and Nicola Procaccini of the Brothers of Italy. The group has six vice-chairmen, each from a different member party.[33] The ECRG’s bureau is made up of 18 MEPs and includes representatives from most, but not all, member parties.[34] Its leadership largely corresponds to the relative size and importance of each party delegation, and it often includes personalities that have earned merits among the ECR ranks. Overall, the imprint of the Polish PiS party, whose representatives hold six out of the roughly 30 positions in the leadership team, is particularly strong.

Ryszard Legutko, a PiS MEP since 2009, is one of the senior operatives in the ECRG and serves as its co-chairman, while also sitting on the ECR Party board of directors. Legutko cut his political teeth as anti-Communist samizdat editor, and today is a professor of philosophy at the Jagiellonian University in Krakow. Known for his reactionary writings, in 2016 Legutko published The Demon in Democracy: Totalitarian Temptations in Free Societies,wherein he draws parallels between Communism and liberal democracy in order to denounce both, for they would advocate multinationalism and deprive nation states of sovereignty.[35] The anti-democratic tirade is supplemented by a long list of reactionary discontents, ranging from secularism and LGBTIQ rights, to immigration—abominations only to be overcome by returning to Catholic constructs, such as eternal truth and firm faith, in the eyes of Legutko. Legutko has a strong footprint in ECR-affiliated organizations that receive support from the Fidesz government in Hungary, such as the Danube Institute and The European Conservative journal, where he is serving as a member of the academic advisory board.[36]

Also, the vice chairmen include some reactionary hardliners, including Hermann Tertsch, an MEP for the Spanish Vox party since 2019, who has been an avid networker among the ECR’s international allies. Tertsch, whose father was deputy head of the Nazi press delegation in Spain during World War II, was one of the founding signatories of the Madrid Charter in 2020.[37] The pamphlet devised by Vox’s think tank, Fundación Disenso, aims to unite the right against the left in Spain and Latin America. The document states that “The Iberosphere … is kidnapped by totalitarian regimes inspired by communism, supported by drug trafficking and allied countries.”[38] The Charter has been signed by right-wing politicians and personalities worldwide, such as Vox leader Santiago Abascal; Prime Minister of Italy and ECR Party President Giorgia Meloni; former Colombian President Andrés Pastrana; Argentinean President Javier Milei; and Brazilian Congressman (and son of the previous president) Eduardo Bolsonaro.

Another radical figure among the ECRG’s vice chairs is the Independent Rob Roos, who has rallied against the Dutch government’s COVID restrictions, and is a vociferous climate-change denier.[39] For example, he claimed recently that the climate emergency is “something that is created in the European Parliament … to push the Green Deal.”[40]

Also, the ECR Group Bureau has some notorious personalities among its ranks, such as Nicolas Bay, a vice chair of the French Reconquest (Reconquête) party, which joined the ECR Group in February 2024.[41] Previously attached to France’s National Rally party, Bay’s immunity was lifted in the European Parliament in February 2023 due to an investigation into suspected provocation of racial hatred.[42] Bay’s parliamentary assistant, Bastien Rondeau-Frimas, is the spokesman of the Institut Iliade, an influential think tank at the heart of France’s far-right resurgence.[43]

The ECR Party

Since the ECR Group focuses on European parliamentary politics, it is much better documented than the ECR Party (ECRP), which does not appear in the political limelight, but rather works in the background to organize political campaigns for itself and its member parties. The ECRP, one of 10 parties in the European Parliament, currently has 14 national member parties.[44]

Registered in Belgium as a nonprofit organization, the ECRP is largely funded by the European Parliament. Subordinated to the ECRPis a political foundation and think tank, New Direction, which also receives EU funding. The ECRP’s mouthpiece is The Conservative, dubbing itself the “ECR Party’s multilingual hub for Centre-Right ideas and commentary,” which has been published since around 2017.[45]

As previously mentioned, in contrast to the ECRG, the ECRP is allowed to fund or organize political campaigns. But its Europarty status has other perks vis-à-vis the group. For example, the factional representation in several other European structures corresponds to the affiliation with the Europarty rather than the group. As such, the ECRP is represented in the European Committee of the Regions and in the NATO Parliamentary Assembly.[46] Within the Council of Europe, the ECRP and the Identity and Democracy Party form the European Conservatives Group and Democratic Alliance, and the ECRP is present in the Congress of Local and Regional Authorities.

Around two-thirds of the member parties of the ECRP overlap with those of the ECRG. Many of the major member parties of the ECRG are also members of the ECRP (with the notable exception of the New Flemish Alliance): Law and Justice, Brothers of Italy, Vox, the Civic Democratic Party, the Sweden Democrats, the Bulgarian National Movement, the National Alliance, and the Electoral Action of Poles in Lithuania. Only some of the smaller member parties adhere to the Europarty, but not the group—mostly those which are not represented with any MEP in the European Parliament: Freedom and Solidarity (Slovakia), Right Alternative (Romania), and the Alternative Democratic Reform Party (Luxembourg).

The ECRP is governed by a party board and a board of directors. The party board is presided over by Italy’s Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni of Fratelli d’Italia, while its vice presidents are Jorge Buxadé of Vox and Radoslaw Fogiel of the Polish Law and Justice party.[47] The secretary general is FdI’s Antonio Giordano. The board of directors has 14 members, some of whom are also among the leadership of the ECR Group, including Ryszard Legutko, Hermann Tertsch, and Nicola Procaccini.

Some of the leading figures in the ECRP leadership have a pertinent past in neofascist organizations and parties, such as Buxadé, who is a self-confessed admirer of José Antonio Primo de Rivera, the founder of the fascist Falange, and has condemned the 1978 Spanish Constitution adopted after the end of the Franco regime.[48] Also, Giorgia Meloni cut her political teeth in the neofascist Italian Social Movement, an early predecessor of Fratelli d’Italia, and many of the FdI leaders proudly look back to the party’s fascist ancestors. FdI has experienced a stellar rise in Italy, and is anticipated to be the biggest delegation in the 2024 EU elections, which adds to the party’s clout among ECR colleagues.

Besides its EU-based member parties, the ECRP lists seven “global partners” on its website, including non-EU and international parties. These comprise notably the US Republican Party, and the Israeli Likud Movement led by Benjamin Netanyahu. The other parties are: Enough is Enough (Serbia); the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (North Macedonia); the Popular Front Party (Belarus); the Republican Party of Albania; and the Ulster Unionist Party (United Kingdom).[49]

New Direction

The ECR Party runs a think tank called New Direction (ND), founded in late 2009, whose operational scope includes cadre and leadership training, the organization of networking and strategizing events, and various publishing endeavors.[50] As such, it plays a central role in the ideological production and formation of the ECR. Compared to the fluctuation within the ECR Group and Party, ND has remained comparably constant.

Thus, although the UK is no longer part of the European Union, British Conservatives still exert a certain influence on ECR policies through ND—for example, by way of the former military intelligence bigwig Geoffrey van Orden, the first president of ND, and currently one of its vice presidents; or Robert Tyler, ND’s senior policy adviser.[51] In 1989, Van Orden was Chief of Staff of the British Sector and head of the military intelligence staff in Berlin when the Wall fell. His final military assignment was at NATO Headquarters in Brussels, where he served as the head of the secretariat for the International Military Staff.

With Margaret Thatcher as founding patroness, a strong proponent of Anglo-American collaboration, New Direction has been considerably influenced by the American right as well. To this day, a multitude of American lobby groups are represented at ND events, including the Heritage Foundation and the Acton Institute, two of the main vehicles used by US megadonors to fund the Christian right in Europe.[52] ND’s events are for the most part geared toward bringing together representatives of organizations associated or sympathizing with ECR member parties, including political think tanks and lobby groups in and around the European Parliament.

European Young Conservatives

The ECR Party also has an affiliated, institutionally separate youth wing, the European Young Conservatives (EYC), which brings together the youth groups of largely, but not exclusively, ECR member parties from across Europe.[53] Because EYC’s major social media accounts have not posted anything since 2021 and its website is currently down, the project seems more or less inactive.[54] Founded in 1993, the EYC preceded the current ECR iteration by more than 15 years, which explains the structural separation. As of 2021, around 25 youth organizations were members of EYC.[55]

From all the ECR substructures, the EYC has the most obvious far-right underbelly, even reaching into the neo-Nazi scene.[56] Like many youth party groups, the EYC is more radical than its parent, and as such a hotbed for far-right youth groups battling over different flavors of nationalism. For example, in 2016, an internal conflict erupted between the civic and ethnic nationalist factions within EYC. The ethnic nationalists were against including Turkish and Israeli member parties, accusing EYC of having “replaced anti-immigration politics with free market capitalism.”[57] The anti-Semitic and Islamophobic debate was publicized by the website altright.com of the neo-Nazi figurehead Richard B. Spencer.[58] As a result, in May 2017 the Finns Party Youth withdrew from EYC in protest, and the Estonian Blue Awakening was expelled from EYC on the basis of its extreme nationalism.[59]

Overall, it appears that the ECR Party’s substructures, such as New Direction and the Young European Conservatives, serve as major interfaces with extra-parliamentary political interest groups, as they largely escape public attention and thus shield the ECR from possible repercussions.

The 2024 European Election

The upcoming European election will take place from June 6 to 9, 2024, and it is expected that the ECR Group will grow by 15% to 20%, from currently 68 MEPs to 80 or more. For one thing, such growth is the result of some of its larger parties having gained considerable ground in the meantime. Furthermore, several parties that are performing well in the polls have announced their intentions to join, or have already joined, the group.

In early 2024, Reconquête became a member of the ECR Group. The French far-right party was founded in 2021 by Éric Zemmour with Marion Maréchal, the ultra-right niece of former National Rally presidential nominee Marine Le Pen, as a fellow campaigner. As of early February 2024, Reconquête was polling at around 6%, which may translate into five seats in the European Parliament.[60] Furthermore, three parties that are expected to win one seat each have pledged to join the ECRG following the election: There is Such a People (Ima takav narod)[61] from Bulgaria, The Bridge (Most) from Croatia, and the National Popular Front (Ethniko Laiko Metopo) from Cyprus.[62] Also the right-wing to far-right Denmark Democrats (Danmarksdemokraterne) have announced that they will join the group in the event they will obtain a seat, although the chances are slim.[63]

In January 2024, it was reported thatthe Hungarian Fidesz was in talks to join ECR after the June election, whose 12 MEPs have been sitting among the Non-Inscrits since they left the EPP in 2021.[64] However, the announcement has led to some frictions within the ECR, with the Sweden Democrats and the Czech Civic Democratic Party threatening to leave the ECR in the event that Fidesz should join.[65] Also the right-wing to far-right Alliance for the Union of Romanians (Alianța pentru Unirea Românilor), which may obtain eight seats following the June election, made their accession to the ECR Group conditional on Fidesz’s not being accepted.[66]

Judging from national polls, with the exception of PiS, most of the leading parties of ECR are expected to gain seats. The party with the biggest anticipated growth is Fratelli d’Italia, which has considerably risen in popularity since the last European election, when it received 6.44%. It currently holds 10 seats in the European Parliament, but with the party polling at 27%, the number may rise to as many as 25.[67] Also, the Vox delegation is expected to grow from four to six MEPs, since it is now polling at 10%, as compared to 6.28% in the last EU election.[68] Furthermore, three parties are expected to gain one seat each: the Sweden Democrats, who received 15.34% (3 seats) in the last EU election, while currently polling at around 21%[69]; the True Finns, who reached 13.8% (2 seats) in the 2019 European election, but lately have been polling at around 18%[70]; and the New Flemish Alliance (3 seats), which is presently polling at around 21%, as compared to 13.73% in the past EU election.[71]

Overall, these gains should more than compensate the losses that some of ECR’s member parties have experienced in the meantime, such as the Polish Law and Justice party. In the last EU election, PiS received 45.38% of the national vote, and it currently holds 25 seats in the European Parliament. With PiS currently polling at 31%, the party delegation may shrink to 15 MEPs in the upcoming legislature.[72] PiS’s losses may also affect the Sovereign Poland party, which had received two seats through its alliance with PiS, but is expected to obtain only one seat following the June election. The party VMRO—Bulgarian National Movement will likely lose its two seats. It had received 7.36% of the national vote in the last EU election; however, as of early 2024 it has been polling at just 0.8%.[73] The other member parties only sent one MEP each. Whether they will be represented in the next legislature is hard to predict, since all of them are minority parties.

Besides the ECR Group, the competing right-wing to far-right ID Group, which currently has 59 MEPs, is expected to grow considerably. Extrapolations from national election results and polls project that the group may obtain over 80 seats.[74] Among the ID member parties which have experienced considerable growth in the latest national polls are the far-right Alternative for Germany (18%),[75] the Belgian Flemish Interest (25%),[76] and last but not least, the Freedom Party of Austria (27%).[77]

Conclusion

In its 15 years of existence, the composition of the ECR has shifted more and more to the right, and so has its politics. In order to obfuscate its radicalization and to provide a respectable façade, the ECR still identifies as center-right and merely conservative, belying the fact that it is rather on the right-wing to far-right end of the political spectrum. Member parties on the national level are advised to do the same regardless of their actual political positioning, all the while most of them retain an extreme-right underbelly.

The past 10 years have already been marked by a considerable shift to the right in the European Parliament, and the coming legislature will likely continue that trend, with the number of MEPs in the ECR Group anticipated to grow to more than 80. Altogether, the right-wing to far-right block could get hold of more than 160 of the 720 seats in Brussels—around 23% of the total vote. Although there are ideological differences between the two major right-wing to far-right groups, ECR and ID, they have come together on single issues put to vote in the European Parliament in the past.

The same applies to the collaboration with the center-right to right-wing EPP, which currently holds 177 seats. Also, the EPP has made common cause with the far right in the past years, just recently in a vote against a nature-restoration bill. The opposition blames the EPP of having made a “rightward shift” and “enabling the normalization of far-right parties.”[78] Overall, the recent closing of ranks between the center right and far right over a number of issues makes a closer collaboration between the camps a distinct possibility in the coming legislature.

Since the European Parliament votes by simple majority, any vote tally over 50% will suffice to decide an issue. An alliance between the center-right to far-right ranks may well reach over 50% of the votes, with MEPs from the Renew Europe Group and the Non-Inscrits providing an additional pool of potential votes—a likely scenario which experts anticipate will facilitate a sharp right turn in EU politics.

[1] Suzanne Lynch, “Europe Swings Right—and Reshapes the EU,” Politico, June 30, 2023, https://www.politico.eu/article/far-right-giorgia-meloni-europe-swings-right-and-reshapes-the-eu/; Simon Hix and Kevin Cunningham, “A Sharp Right Turn: A Forecast for the 2024 European Parliament Elections,” EU Reporter, January 25, 2024, https://www.eureporter.co/politics/european-parliament-2/2024/01/25/a-sharp-right-turn-a-forecast-for-the-2024-european-parliament-elections/.

[2] MEPs of the European Conservatives and Reformists Group, European Parliament, accessed April 9, 2024, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/meps/en/search/advanced?name=&euPoliticalGroupBodyRefNum=4271; “EU Election Projection 2024,” Europe Elects, accessed April 15, 2024, https://europeelects.eu/ep2024/; “Poll of Polls: EU Election 2024,” Politico, accessed April 15, 2024, https://www.politico.eu/europe-poll-of-polls/european-parliament-election/.

[3] “The ECR Group is a centre-right political group in the European Parliament …” See “Who We Are,” ECR Group, accessed February 23, 2024, https://ecrgroup.eu/ecr.

[4] Martin H. M. Steven, The European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR): Politics, Parties and Policies (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 2020).

[5] “The End of a Loveless Marriage: Cameron Plans EPP Exit,” European Foundation, April 21, 2009, https://europeanfoundation.org/the-end-of-a-loveless-marriage-cameron-plans-epp-exit/.

[6] Martin Banks, “Tories Stay in ‘Marriage of Convenience’ with EPP,” European Sources Online, December 2, 2004, https://www.europeansources.info/record/tories-stay-in-marriage-of-convenience-with-epp/.

[7] Melissa Kite, “Cameron Gives Hague Month to Get MEPs out of Brussels Group,” Telegraph, June 11, 2006, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1520953/Cameron-gives-Hague-month-to-get-MEPs-out-of-Brussels-group.html; “Tories Leaving Europe’s EPP Group,” BBC, March 11, 2009, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/politics/7938482.stm.

[8] “In Full: Cameron Euro Declaration,” BBC, July 13, 2006, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/politics/5175994.stm.

[9] BBC, “Tories Leaving Europe’s EPP Group.”

[10] “The Prague Declaration,” ECR Group, December 17, 2013, https://ecrgroup.eu/article/the_prague_declaration.

[11] “Conservative MEPs Form New Group,” BBC, June 22, 2009, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/8112581.stm.

[12] Martin Banks, “British Tories Fight It Out for Leadership of New Eurosceptic Group,” The Parliament, July 9, 2009, https://web.archive.org/web/20091120124425/http://www.theparliament.com/no_cache/latestnews/news-article/newsarticle/british-tories-fight-it-out-for-leadership-of-new-eurosceptic-group/.

[13] Rajeev Syal, “Conservatives’ EU Alliance in Turmoil as Michał Kamiński Leaves ‘Far Right’ Party,” Guardian, November 22, 2010, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2010/nov/22/conservatives-eu-alliance-michal-kaminski.

[14] David Charter, “Tory Party Upsets Czech Partners with Choice of Anti Federalist MEPs,” Times, October 19, 2023, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/tory-party-upsets-czech-partners-with-choice-of-anti-federalist-meps-7rb2z32hnrp.

[15] “When Dave Met Bart,” Politico, March 23, 2011, https://www.politico.eu/article/when-dave-met-bart/.

[16] Joaquín Martín-Cubas et al., “The ‘Big Bang’ of the Populist Parties in the European Union: The 2014 European Parliament Election,” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 32, no. 2 (April 2019): 168–190; Chih-Mei Luo, “The Rise of Populist Right-Wing Parties in the 2014 European Parliament: Election and Implications for European Integration,” European Review 25, no. 3 (July 2017): 406–422.

[17] “Results of the 2014 European Elections,” European Parliament, accessed February 6, 2024, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/elections2014-results/en/election-results-2014.html; Laurens Cerulus, “Cameron’s Group Challenges Liberals as Kingmakers in New Parliament,” Euractiv, June 5, 2014, https://www.euractiv.com/section/elections/news/cameron-s-group-challenges-liberals-as-kingmakers-in-new-parliament/.

[18] Nicholas Watt, “David Cameron Accused over ‘dubious’ European Union Partners,” Guardian, June 5, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2014/jun/05/david-cameron-under-fire-as-dpp-and-true-finns-enter-ecr-group.

[19] Alex Barker, “MEPs with Criminal Records Join Tories’ Eurosceptic Group,” Financial Times, June 4, 2014, https://www.ft.com/content/d0b45ce0-ec11-11e3-a9e3-00144feabdc0.

[20] David Dunne, “Finns Party MP Remains Defiant after Race Hate Conviction,” Helsinki Times, June 20, 2012, http://www.helsinkitimes.fi/helsinkitimes/2012jun/issue24-255/helsinki_times24-255.pdf.

[21] Barker, “MEPs with Criminal Records Join Tories’ Eurosceptic Group.”

[22] Alexander Häusler, Rainer Roeser, and Lisa Scholten, “Programmatik, Themensetzung und politische Praxis der Partei ‘Alternative für Deutschland’ (AfD),” Heinrich Böll Foundation, May 2, 2016), 22–23, https://www.slu-boell.de/de/2016/08/26/programmatik-themensetzung-und-politische-praxis-der-partei-alternative-fuer-deutschland.

[23] James Crisp, “AfD Links to Austrian Far-Right ‘Final Straw’ for ECR MEPs,” Euractiv, March 9, 2016, https://www.euractiv.com/section/social-europe-jobs/news/afd-links-to-austrian-far-right-final-straw-for-ecr-meps/.

[24] Jennifer Rankin, “Daniel Hannan’s MEP Group Told to Repay €535,000 in EU Funds,” Guardian, December 13, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2018/dec/13/daniel-hannan-mep-group-told-to-repay-half-a-million-in-eu-funds.

[25] Arne Lapidus, “Här bildar nazisterna partiet SD–i Malmö,” Expressen, September 14, 2014, https://www.expressen.se/kvallsposten/har-bildar-nazisterna-partiet-sd–i-malmo/.

[26] Theodoros Benakis, “Dutch and Greek Far-Right Parties Join ECR Group,” European Interest, June 6, 2019, https://www.europeaninterest.eu/article/dutch-greek-far-right-parties-join-ecr-group/.

[27] Rebecca Ritters, “Germany’s AfD Joins Italy’s League to Form New Group,” Deutsche Welle, April 8, 2019, https://www.dw.com/en/germanys-afd-joins-italys-league-in-new-populist-coalition/a-48249992.

[28] “Legutko: The ECR Will Stand by Ukraine until Russia Is Defeated and beyond,” ECR Group, February 9, 2023, https://ecrgroup.eu/article/legutko_the_ecr_will_stand_by_ukraine_until_russia_is_defeated_and_beyond.

[29] Nicholas Camut, “Far-Right Finns Party Moves to ECR Group in EU Parliament,” Politico, April 5, 2023, https://www.politico.eu/article/far-right-finns-party-ecr-european-conservatives-and-reformists-group-parliament/.

[30] Iva Dzhunova, “European Politics: National Parties, European Parties, Political Groups,” Shaping Europe, January 30, 2024, https://shapingeurope.eu/en/european-politics-national-parties-european-parties-political-groups/.

[31] “MEPs by Member State and Political Group,” European Parliament, accessed April 15, 2024, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/meps/en/search/table.

[32] “2019 European Election Results,” European Parliament, October 23, 2019, https://europarl.europa.eu/election-results-2019/en/; “Redistribution of Seats in the European Parliament after Brexit,” European Parliament, January 31, 2020, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20200130IPR71407/redistribution-of-seats-in-the-european-parliament-after-brexit.

[33] Assita Kanko, N-VA (Belgium); Beata Szydło, PiS (Poland); Hermann Tertsch, Vox (Spain), Rob Roos, Independent (Netherlands); Charlie Weimers, SD (Sweden); and Veronika Vrecionová, ODS (Czech Republic).

[34] “Structure,” ECR Group, accessed February 8, 2024, https://ecrgroup.eu/ecr/structure.

[35] Ryszard Legutko, The Demon in Democracy: Totalitarian Temptations in Free Societies (New York and London: Encounter Books, 2016).

[36] Search Results for “Ryszard Legutko,” Danube Institute, accessed February 9, 2024, https://danubeinstitute.hu/en/search/result?search=Ryszard+Legutko+; “About,” The European Conservative, accessed February 9, 2024, https://europeanconservative.com/about/.

[37] Stefan Müller, David Schriffl, and Adamantios Skordos, Heimliche Freunde: Die Beziehungen Österreichs zu den Diktaturen Südeuropas nach 1945: Spanien, Portugal, Griechenland (Vienna and Cologne: Böhlau Verlag, 2016), 27.

[38] “Madrid Charter: In Defense of Freedom and Democracy in the Iberosphere,” Fundación Disenso, October 26, 2020, https://fundaciondisenso.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/FD-Carta-Madrid-AAFF-EN-V7.pdf.

[39] Sergio Velasco, “Freedom or Totalitarianism in Europe? – An Interview With Rob Roos,” The Long Brief, June 15, 2023, https://longbrief.com/rob-roos-interview-freedom-covid-netherlands-farmers-party/; “Rob Roos (JA21) naar rechter om coronapasplicht EU-parlement,” Leidsch Dagblad, November 5, 2021, https://www.leidschdagblad.nl/cnt/dmf20211105_26057476.

[40] Zsófia Tóth-Bíró, “Looking Beneath the Surface: Interview with Rob Roos about Climate Change, AI and Digital Green Pass,” Hungarian Conservative, May 4, 2022, https://www.hungarianconservative.com/articles/interview/looking-beneath-the-surface-interview-with-rob-roos-about-climate-change-ai-and-digital-green-pass/.

[41] Kjeld Neubert and Théophane Hartmann, “Zemmour’s Party Joins ECR to Boost Grand Right-Wing Coalition,” Euractiv, February 7, 2024, https://www.euractiv.com/section/elections/news/zemmours-party-joins-ecr-to-boost-grand-right-wing-coalition/.

[42] “Ce lieutenant d’Éric Zemmour pourra être poursuivi pour incitation à la haine raciale,” Le HuffPost, February 2, 2023, https://www.huffingtonpost.fr/politique/article/nicolas-bay-lieutenant-d-eric-zemmour-pourra-etre-poursuivi-pour-provocation-a-la-haine-raciale_213563.html.

[43] “Nicolas Bay: Assistants,” European Parliament, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/meps/en/124760/NICOLAS_BAY/assistants.

[44] The website does not yet include the French Reconquest party, although it has reportedly joined the ECRP. “About,” ECR Party, accessed April 15, 2024, https://ecrparty.eu/about/; “French Reconquête! Party Joins Family of European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR),” Agence Europe, February 8, 2024, https://agenceurope.eu/en/bulletin/article/13345/22.

[45] First archived copy of The Conservative, February 1, 2017, https://web.archive.org/web/20170201053117/https://www.theconservative.online/.

[46] ECR Group in the European Committee of the Regions, accessed February 29, 2024, https://www.ecrcor.eu/.

[47] ECR Party, “About.”

[48] Miguel González, “Jorge Buxadé Villalba: un falangista en el Parlamento Europeo,” El País, May 10, 2019, https://elpais.com/internacional/2019/05/09/actualidad/1557417795_838959.html.

[49] ECR Party, “About.”

[50] New Direction, accessed February 7, 2024, https://newdirection.online.

[51] “About,” New Direction, accessed September 15, 2023, https://newdirection.online/about.

[52] Neil Datta, “Tip of the Iceberg: Religious Extremist Funders against Human Rights for Sexuality and Reproductive Health in Europe 2009–2018” (Brussels: European Parliamentary Forum for Sexual and Reproductive Rights, June 2021), https://www.epfweb.org/sites/default/files/2021-06/Tip%20of%20the%20Iceberg%20June%202021%20Final.pdf.

[53] European Young Conservatives, archived copy from October 18, 2021, https://web.archive.org/web/20211018222907/https://www.eycorganisation.com/.

[54] European Young Conservatives Twitter account, https://twitter.com/eycorganisation; European Young Conservatives Facebook account, https://www.facebook.com/eyconservatives/.

[55] “Parties,” European Young Conservatives, archived copy from September 1, 2021, https://web.archive.org/web/20210917160149/https://www.eycorganisation.com/parties.

[56] Pēteris F. Timofejevs and Louis John Wierenga, “Making Tomorrow’s Leaders: The Transnationalism of Radical Right Youth Organizations in the Baltic Sea Area, 2015–2019,” Baltic Worlds XVI, no. 3 (2023): 62–77, http://umu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1790543/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

[57] Ruben Kaalep, “Estonian Blue Awakening Gives European Young Conservatives 7 Days to Stop Their Cuckish Ways,” AltRight.com, June 12, 2017, https://altright.com/2017/06/12/estonian-blue-awakening-gives-european-young-conservatives-7-days-to-stop-their-cuckish-ways/.

[58] Kaalep, “Estonian Blue Awakening Gives European Young Conservatives 7 Days to Stop Their Cuckish Ways.”

[59] “The Finns Party Youth Leaves European Young Conservatives,” Purussuomalets Nuoret, May 18, 2017, https://web.archive.org/web/20190513142735/https://www.ps-nuoret.fi/uutiset/the-finns-party-youth-leaves-european-young-conservatives/; “EKRE’s Youth Organization Thrown Out of European Young Conservatives,” Estonian Public Broadcasting Service, accessed October 23, 2019, https://news.err.ee/602871/ekre-s-youth-organization-thrown-out-of-european-young-conservatives.

[60] Kjeld Neubert and Théophane Hartmann, “Zemmour’s Party Joins ECR to Boost Grand Right-Wing Coalition,” Euractiv, February 7, 2024, https://www.euractiv.com/section/elections/news/zemmours-party-joins-ecr-to-boost-grand-right-wing-coalition/; Europe Elects, “EU Election Projection 2024.”

[61] “Bulgaria’s ITN Wants to Join ECR Party Family,” Central European Times, December 4, 2023, https://centraleuropeantimes.com/2023/12/bulgarias-itn-wants-to-join-far-right-eu-party/.

[62] Europe Elects, “EU Election Projection 2024.”

[63] Per Bang Thomsen, “Danmarksdemokraterne har fundet sine allierede i EU. Og én af dem er Sverigedemokraterne,” DR, April 12, 2024, https://www.dr.dk/nyheder/udland/eu/danmarksdemokraterne-har-fundet-sine-allierede-i-eu-og-en-af-dem-er.

[64] Eddy Wax, “Viktor Orbán Has Not Asked to Join Right-Wing EU Parliament Group, Spokesperson Says,” Politico, January 12, 2024, https://www.politico.eu/article/viktor-orban-right-wing-ecr-group-european-parliament/.

[65] Eddy Wax, “Sweden Democrats Threaten to Quit Right-Wing EU Group if Orbán Joins,” Politico, February 9, 2024, https://www.politico.eu/article/sweden-democrats-threaten-to-quit-right-wing-eu-group-erc-if-orban-joins/; Aneta Zachová, “We Do Not Want Orban in ECR, Says Czech Conservative,” Euractiv, February 7, 2024, https://www.euractiv.com/section/politics/news/we-do-not-want-orban-in-ecr-says-czech-conservative/.

[66] Max Griera, “Romania’s Far-Right Threatens to Pull Out of ECR Group in New Blow to Orbán,” Euractiv, February 12, 2024, https://www.euractiv.com/section/elections/news/romanias-far-right-threatens-to-pull-out-of-ecr-group-in-new-blow-to-orban/; Europe Elects, “EU Election Projection 2024.”

[67] “National Results Italy: 2019 Election Results,” European Parliament, accessed October 12, 2023, https://europarl.europa.eu/election-results-2019/en/national-results/italy/2019-2024/; “Poll of Polls: Italy,” Politico, accessed April 15, 2024, https://www.politico.eu/europe-poll-of-polls/italy/; Europe Elects, “EU Election Projection 2024.”

[68] “National Results Spain: 2019 Election Results,” European Parliament, accessed October 12, 2023, https://europarl.europa.eu/election-results-2019/en/national-results/spain/2019-2024/; “Poll of Polls: Spain,” Politico, February 16, 2022, https://www.politico.eu/europe-poll-of-polls/spain/; Europe Elects, “EU Election Projection 2024.”

[69] “National Results Sweden: 2019 Election Results,” European Parliament, accessed October 12, 2023, https://europarl.europa.eu/election-results-2019/en/national-results/sweden/2019-2024/; “Poll of Polls: Sweden,” Politico, accessed April 15, 2024, https://www.politico.eu/europe-poll-of-polls/sweden/; Europe Elects, “EU Election Projection 2024.”

[70] “National Results Finland: 2019 Election Results,” European Parliament, accessed October 12, 2023, https://europarl.europa.eu/election-results-2019/en/national-results/finland/2019-2024/; “Poll of Polls: Finland,” Politico, accessed April 15, 2024, https://www.politico.eu/europe-poll-of-polls/finland/; Europe Elects, “EU Election Projection 2024.”

[71] “National Results Belgium: 2019 Election Results,” European Parliament, accessed October 12, 2023, https://europarl.europa.eu/election-results-2019/en/national-results/belgium/2019-2024/; “Poll of Polls: Belgium,” Politico, accessed April 15, 2024, https://www.politico.eu/europe-poll-of-polls/belgium/.

[72] “National Results Poland: 2019 Election Results,” European Parliament, accessed October 12, 2023, https://europarl.europa.eu/election-results-2019/en/national-results/poland/2019-2024/; “Poll of Polls: Poland,” Politico, accessed April 15, 2024, https://www.politico.eu/europe-poll-of-polls/poland/; Europe Elects, “EU Election Projection 2024.”

[73] “National Results Bulgaria: 2019 Election Results,” European Parliament, accessed October 12, 2023, https://europarl.europa.eu/election-results-2019/en/national-results/bulgaria/2019-2024/; “Poll of Polls: Bulgaria,” Politico, accessed April 15, 2024, https://www.politico.eu/europe-poll-of-polls/bulgaria/.

[74] Europe Elects, “EU Election Projection 2024”; “Poll of Polls: European Parliament Election,” Politico, accessed April 15, 2024, https://www.politico.eu/europe-poll-of-polls/european-parliament-election/.

[75] “Poll of Polls: Germany,” Politico, accessed April 15, 2024, https://www.politico.eu/europe-poll-of-polls/germany/.

[76] Politico, “Poll of Polls: Belgium.”

[77] “Poll of Polls: Austria,” Politico, accessed April 15, 2024, https://www.politico.eu/europe-poll-of-polls/austria/.

[78] Eddy Wax, “Socialists Tone Down Attacks on Conservatives and Liberals in EU Election Manifesto,” Politico, February 29, 2024, https://www.politico.eu/article/socialists-tone-down-attacks-conservatives-liberals-eu-election-manifesto/.