Blurring Boundaries: The Catholic Traditionalist and Identitarian Nexus in the Contemporary French Far Right

by Périne Schir

IERES Occasional Papers, no. 30, February 2025 “Transnational History of the Far Right” Series

Photo: Made by John Chrobak.

The contents of articles published are the sole responsibility of the author(s). The Institute for European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies, including its staff and faculty, is not responsible for any inaccurate or incorrect statement expressed in the published papers. Articles do not necessarily represent the views of the Institute for European, Russia, and Eurasian Studies or any members of its projects.

©IERES 2025

On December 11, 2023 French Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin announced plans to dissolve Academia Christiana (AC) as an extremist organization which threatened the democratic order and for links to other extremist organizations.[1] Academia Christiana describes itself as dedicated to spiritual, moral, and educational training. This announcement came as a surprise to both the French and international media, which was struck by the targeting of a seemingly “peaceful” Catholic association as part of a broader wave of government-forced dissolutions of far-right entities. Although the AC presents itself as a benign organization,[2] the Interior Ministry claims it “legitimizes physical violence” and encourages its supporters “to arm themselves and go on a crusade.”[3] Several of its members have reportedly been flagged for extremist views and are under close surveillance by French intelligence.[4]

But more importantly, the AC represents a new phase in the evolution of the French far right, situated at the crossroads of Catholic traditionalism and identitarianism. Since 2013—especially after the dissolution of “La Manif pour Tous,” a Catholic-led movement opposing same-sex marriage—an alliance has developed between identitarians and Catholic traditionalists.[5]

Identitarians, typically associated with Génération Identitaire—an organization created in 2012 and dissolved by the Interior Ministry in 2021[6]—trace their roots back to Bloc Identitaire. Bloc Identitaire, in turn, is a reformed Unité Radicale, which emerged in 1998 as an alliance between Groupe Union Défense (GUD) and Troisième Voie, the latter a nationalist-revolutionary movement later renamed Jeune Résistance. The identitarian ideology seen in groups like the AC today is thus a direct descendant of the nationalist-revolutionary ideologies once promoted by the GUD. Over time, the identitarian movement has adapted to the social climate, shifting its focus away from opposition to American imperialism—the primary enemy in the nationalist-revolutionary circles of the 1980s—toward opposition to Islamism and Muslim immigration.[7]

Meanwhile, the Catholic traditionalist sphere has been heavily influenced by Action Française (AF), one of France’s oldest far-right movements, known for its anti-Semitic positions dating back to the Dreyfus affair. Established as nationalist and anti-Semitic, the AF promoted “integral nationalism” and became a major force in shaping French and European far-right ideology in the 20th century. The AF’s historical links with fascist movements in Germany and Italy positioned it as a bridge between monarchism, ultranationalism, and Catholic traditionalism. The first section of this paper explores the origins of the AF, its ideological intersections with German Nazism and Italian fascism, and its evolving current activities.

Today, the lines between these two previously separate far-right factions have blurred, with new shared platforms emerging. In the second section, this paper examines two such examples: the AC, which acts as an ideological bridge between traditionalist Catholics and identitarians, and the GUD’s fourth generation, which, having absorbed whole chapters of the former AF, has served as a tool for the creation of a new hybridized movement. Through an analysis of specific collaborative efforts and the networks that sustain these ties, the paper sheds light on the broader dynamics of France’s contemporary far right, where ideological and organizational boundaries are increasingly fluid.

Action Française: Origins and Ideology

The Dreyfus Affair and the Birth of Action Française

Action Française was created during and because of the Dreyfus Affair, a political crisis (1894–1906) that erupted after army captain Alfred Dreyfus, on December 22, 1894, had been convicted of treason for allegedly selling military secrets to the Germans and sentenced to life imprisonment. It polarized the French public.

On the one hand, the anti-Dreyfusards supported the conviction and were willing to believe in the guilt of Dreyfus, who was Jewish. Indeed, much of the propaganda for the anti-Dreyfusard camp was supplied by anti-Semitic groups (especially the newspaper La Libre Parole of Édouard Drumont), to whom Dreyfus symbolized the supposed disloyalty of French Jews.

The Dreyfusard (pro-Dreyfus) side wanted to reverse the sentence, as evidence pointed to the guilt of another French officer, Ferdinand Walsin-Esterhazy. The accusations against Esterhazy resulted in a court-martial that acquitted him of treason on January 11, 1898 which effectively precluded a revision of the Dreyfus conviction. Two days later, to protest the verdict, the novelist Émile Zola wrote a letter titled “J’accuse,” attacking the army’s uncovered antisemitism and its mistaken conviction of Dreyfus. In August 1898, an important document implicating Dreyfus was found to be a forgery, yet he still was found guilty by the court. At that point, left-wing MPs started to recognize that the increasingly vocal far right posed a threat to the parliamentary regime. They formed a left-wing coalition and then a new government cabinet. Because of them, the president pardoned and rehabilitated Dreyfus.

Charles Maurras (left) and Léon Daudet (right) at the National Festival of Joan of Arc and Patriotism, Paris, Place Saint-Augustin, May 9, 1926.

Source of the photo: Gallica Digital Library

The following year, in 1899, the AF was created to gather the anti-Semitic anti-Dreyfusards under one roof. But this story goes far beyond the life story of Dreyfus, because it forced the left to unite, marking a new phase in the history of French politics. Indeed, the new left-wing cabinet then pursued an anticlerical policy that culminated in the formal separation of church and state in 1905. Finally, by intensifying antagonisms between right and left, and by forcing individuals to choose sides, the Dreyfus affair made a lasting impact on the way French people perceived politics. From then on, French politics featured two blocs: the far right on one side, and the left on the other. While “left–right” terminology found its antecedents in the physical seating arrangement of the French National Assembly of 1789, where supporters of the Ancien Regime sat on the president’s right and supporters of the Revolution to his left, it was during this period nearly a century later that the French left-right divide, as we understand it today, was created. It was also at this time that the extreme right we know today appeared.

The AF had several organizational forms throughout its history: In April 1898, Henri Vaugeois and Maurice Pujo created a “comité d’Action Française,” a private committee, i.e. a small group of intellectuals who met regularly at the Café de Flore. The AF would not become a movement open to the public until the following year. At its first conference on June 20, 1899, Vaugeois defined the purpose of the AF and the meaning of his commitment: “All the evil from which the country suffers,” Vaugeois saw as attributable to “the Protestant spirit, the Masonic spirit and above all to the Jewish spirit, which, for some years now, has dominated all French politics.”[8] At that point, the AF had become a public movement, but it was not yet a political organization.

The movement’s first magazine, a fortnightly called the Revue d’Action Française, was created the following month, in July 1899. Anti-Semitism was, from the start, one of its driving forces. In one of the first articles, published on August 1, 1899, the AF’s aims are defined as follows: “It will therefore first fight the defenders of the sad Captain [Dreyfus]. […] It will have at heart […] to justify and maintain the instinct of repulsion, so healthy, so cheerful, of the French People against the Jew. Anti-Semitism will have thoughtful friends here, who will strive to deepen and clarify its historical and natural legitimacy.” We will argue that the Rights of Man must be carefully measured against certain men.”[9]

In 1905, Maurras founded the “Ligue d’Action Française” with Vaugeois as president, the AF’s first fully-fledged political organization. The following year, in February 1906, the AF set up an institute, meant as a training school for its cadres, a “counter-Sorbonne.” The idea was to teach the militant public a university curriculum different from that of the classic university, which was accused of dispensing knowledge with a left-wing bias.

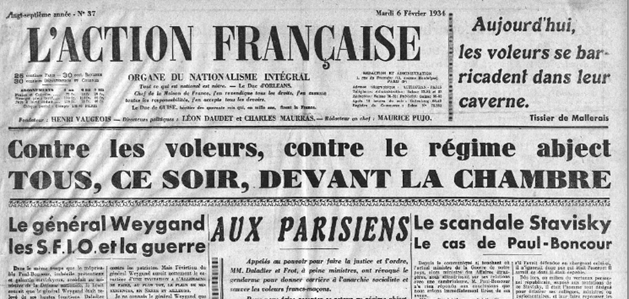

The AF newspaper of February 6, 1934, headlined: “Against the thieves, against the despicable regime. everyone, tonight, in front of the chamber.”

Source: Retronews

The fortnightly magazine was replaced in March 1908 by a daily that would appear until 1944, called Action française quotidienne, organe du nationalisme intégral. It became the leading forum for anti-Semitism and radical nationalism in France, far ahead of Édouard Drumont’s La Libre Parole.[10] The same year, in November 1908, the “Fédération nationale des Camelots du roi” was created by Maxime Real del Sarte as a youth section of the AF. It was initially intended to sell the newspaper, but the Camelots soon gained fame for their recurrent use of violence, particularly against leftists, which made it look increasingly like a paramilitary organization.

Without a newspaper appearing every day to relay information about the league’s campaigns and keep its admirers on their toes, the AF would never have had the audience it did.[11] Thanks to its daily newspaper, the AF gradually extended its influence over a large part of the right and far right—the paper aimed both at the country’s conservative elites and at activists in the royalist movement—until the 1940s.

The broad goal of the paper was the daily denunciation and stigmatization of the Jews, going as far as calls for murder. Maurras, for example, called Léon Blum a “human detritus,” “a man to be shot, but in the back,” which led to a physical attack on Blum in February 1936, earning the AF leader an eight-month prison sentence and incarceration. Such was the role of the AF newspaper: to maintain a sense of urgency among their followers, to give readers daily reasons to be indignant, to mobilize militants around scandals and despicable enemies, hence the choice of rhetorical violence against easy scapegoats, such as the Jewish politician Abraham Schrameck or Blum.

Although the AF is best known for its newspaper and ideological work, another crucial aspect of its operations was violent activism.

This began with the Camelots du Roi: In 1908, the AF set out to build a militant arm. Maxime Real del Sarte served as president, Henry des Lyons as national secretary, and Maurice Pujo managed relations between the Camelots and the main AF organization, overseeing discipline and strategy. The group’s name, Camelots, originated from their early role as street vendors of AF newspapers, selling copies in the streets of Paris and outside churches. Despite this innocuous beginning, they quickly evolved into a paramilitary force and political enforcers, often physically attacking opponents. For example, they targeted history professor Amédée Thalamas after he minimized Joan of Arc’s political importance during the Hundred Years’ War—a figure highly revered by the far right, then and now.[12] They also launched an anti-Semitic campaign against law professor Gérard Lyon-Caen, who was Jewish.

Another prominent example of the AF’s violent activism was its role in the 1934 Stavisky riots, an iconic and mythologized moment in French fascist history. Because of that, it is challenging to separate myth from fact. As historian Brian Jenkins describes, it was “Almost as if Mussolini’s ‘March on Rome’ (October 1922) and Hitler’s failed Munich putsch (November 1923) were seen as the template for the ‘fascist seizure of power’” in France. The riots were sparked by growing public outrage over alleged governmental complicity in financial scandals involving Alexandre Stavisky, a Jewish émigré. This was compounded by Prime Minister Édouard Daladier’s decision to dismiss the popular Paris police chief Jean Chiappe, who was known to be sympathetic to far-right movements.

In response, the AF called for a demonstration to take place on the evening of February 6, 1934 (see photo above). By nightfall, an estimated 40,000 demonstrators surrounded the Chamber of Deputies, demanding Daladier’s resignation. Clashes between the far-right protesters and the police quickly escalated, leading to what would become the bloodiest civil protest in France since the Paris Commune of 1871, with 15 dead and over 1,400 injured. The immediate outcome was the resignation of Daladier, who was replaced by Gaston Doumergue, whose government took a more authoritarian stance that was notably more accommodating to far-right groups.

Politically, the February 6 riots had far-reaching consequences. On the right, it emboldened groups pushing for a more authoritarian government, while on the left, it convinced the French Communist Party (PCF) and other progressive forces that the republic was under threat. This conclusion catalyzed the formation of the anti-fascist Popular Front, an alliance of leftist parties that united to contest the 1936 legislative election. The Popular Front legacy remains significant even today: In 2024, left-wing and far-left parties announced the creation of the New Popular Front in response to the surprise dissolution of parliament initiated by President Macron amid a surge in far-right popularity.

Another significant example of the AF’s violent activism was its link to LaCagoule. On December 9, 1935, a faction of the Camelots du Roi in Paris sent a letter to the AF leadership, accusing it of allowing the movement to decline. Among the signatories were Eugène Deloncle, Jean Filiol, and Aristide Corre, who were soon expelled from the organization. They went on to form La Cagoule, a clandestine political and paramilitary group known for using terrorist methods. After France’s defeat and the armistice of 1940, many former Cagoulards, including Deloncle, aligned with the Vichy regime. They founded the Mouvement Social Révolutionnaire in 1940, which later merged with Marcel Déat’s Rassemblement National Populaire (RNP), the first collaborationist party in France. Some members of La Cagoule even joined the Legion of French Volunteers (LVF)—which fought with the German Wehrmacht and SS units during World War II—with Deloncle serving on its central recruitment committee. After Cagoulard Jean Filiol’s attempted assassination of Léon Blum on February 13, 1936, the minister of the interior dissolved both the Camelots du Roi and the AF league. However, AF’s daily newspaper and institute continued to operate.

Action Française between German Nazism and Italian Fascism

Converting his AF friends to monarchism with his book Enquête sur la Monarchie (1901), Charles Maurras defended a particular type of monarchism, called “integral nationalism,” which combines corporatism, anti-Semitism, anti-Germanism with criticism of parliamentarianism and a rightwing neo-feudalist critique of the market economy.

Yet in the early years of the 20th century, Maurras was not the leading figure in the intellectual and political space of nationalism, and had to play on anti-Semitism as a political strategy to exist as a distinct brand on the Right. First, the Dreyfus affair was the Achilles’ heel of the republican regime, revealing its weaknesses and the “maneuvers” of the Jews. This is why Maurras and the AF never stopped talking about it, even after Dreyfus was found not guilty and pardoned.

Second, AF leaders believed in the mobilizing potential of anti-Semitism. Indeed, the anti-Dreyfusard camp embraces all the currents of nationalism, with only a few of them being royalists. Anti-Semitism was a rallying cry and therefore seen as a means of subverting and taking control of the nationalist space.[13]

Maurras had been seeking to distinguish himself from classic anti-Semitic figures like Drumont by attempting to present his anti-Semitism within a political rather than biological context: Maurras proposed an “antisemitism of the state,” which was supposedly non-biological and close to xenophobia, versus classical “antisemitism of the skin,” which was biological and racist. From then on, Jews would be attacked for their place in the State: A Jew was not, and could not be, a Frenchman. The doctrine of “state anti-Semitism,” theorized in the early 1910s, could be summed up in a single proposition: eliminate the Jew by stripping him of his “fictitious French nationality” and replacing him with the status of eternal foreigner. Maurras therefore advocated for the denaturalization of all Jewish people, which was already a measure put forward in the program drawn up by René de La Tour du Pin and Albert de Mun in 1889.[14]

However, state anti-Semitism should not be necessarily considered a more “moderate” doctrine than classical biological anti-Semitism. The former refers to a legal category (nationality) instead of a biological one (skin color or genes), but it simply infers that the state will solve the “Jewish problem” with legal measures.[15]

The AF offices in Lyon during World War II

Source: Wikimedia

During the interwar period, Maurras’ prose accustomed AF readers to an anti-Semitism that attempted to be all the more legitimate for its faux-rational appearance. In far-right opinion and among large swaths of the right, Maurras’s articles made it self-evident that the Jewish question needed to be “solved”—in other words, that Jewish origins needed to be reified as a problem. They also proposed “solutions,” including the denaturalization of French Jews, and a special “status” with professional limitations and prohibitions. These two options, theorized in the pages of the AF newspaper for nearly three decades, were the ones that caught the attention of the Vichy government in the summer of 1940.[16]

The AF was influential in ideological production but remained on the fringe of politics, apart from the period from 1919 to 1925, when Daudet sat as a deputy in the so-called “blue horizon chamber” and, of course, during the Vichy regime.[17]

During the Nazi occupation, Maurras rose to prominence, having joined the Académie française in 1938, and became an advisor to Marshal Pétain. The offices of the daily AF newspaper were moved to Limoges and then Lyon. Banned in the occupied zone, the royalist daily was subject to Vichy censorship. But lavish donations enabled the newspaper to live largely without government subsidies.

In the world of the Vichy press, the paper enjoyed a special status. Marshal Pétain admired Maurras and received him as early as the end of June 1940—i.e. a few days after Pétain signed the Armistice of June 22, 1940 establishing a German occupation zone in northern and western France that encompassed about three-fifths of France’s territory—Maurras declares: “Fou, et fou à lier, tout quel Français qui voudrait substituer son jugement à celui qu’ont émis les compétences militaires des Pétain et des Weygand,” i.e. Pétain and Weygand know better than anyone else what needs to be done, their intentions are pure, their probity unblemished, and they are free in their movements and decisions. For this reason, Maurras and the AF campaigned against the Resistance but were in favor of compulsory labor service (STO).

During the occupation, Maurras’ anti-Jewish ideas were implemented by the Vichy government, namely the first statute on Jews issued by Marshal Pétain’s government in Vichy in October 1940, which eliminated Jews from state positions.[18] Like other newspapers of the period, that of the AF hardly ever mentions the policy of arresting and deporting Jews. It does, however, allusively justify it from time to time. In September 1942, journalist Frédéric Delebecque, a member of the “comité Directeur” of the AF movement, noted that “since the Jews behave like enemies of France, it is fair and logical to treat them as such.”

The creation of a political administration, the General Commissariat for Jewish Questions (CGQJ), at the end of March 1941, also was a full victory for the AF. Indeed, three successive heads of the CGQJ all had links with the AF: Xavier Vallat and Darquier de Pellepoix were both loyal readers of the AF daily and close to AF circles; the third commissioner, Charles Du Paty de Clam, was also close to AF circles, while his father—the famous officer who obtained Dreyfus’s “confession” in 1894—was a close friend to AF leaders in the years 1900–1910.

Finally, it is also worth noting that the new AF newspaper offices in Lyon were shared with Milice, a paramilitary organization created in 1943 by the Vichy régime with German aid to help fight against the Resistance during World War II. As auxiliaries to the Gestapo the militiamen took part in hunting down Jews, Resistance fighters, STO draft dodgers and all other “deviants” denounced by the Nazi and Vichy regime. Indeed, there are profiles that show the fluidity between these different circles. Take, for example, Joseph Lécussan, a former AF militant who passed through the Cagoule, CGQJ, and then Milice.

Many Milice figures were later convicted of collaboration. Maurras was convicted of committing high treason and sharing intelligence with the enemy and sentenced to life imprisonment. He was pardoned for health reasons shortly before his death in 1952. In June 1947, the AF was reconstituted around Maurice Pujo and Georges Calzant, who founded the “Restauration nationale” movement, the original name having been banned. They published the journal Aspects de la France, using the initials of the AF.

During World War II, the Vichy government engaged in extensive collaboration with both Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy.[19] Vichy diplomacy involved balancing these alliances while aiming to protect French sovereignty against Italian territorial claims on southeastern France and Corsica.

Maurras, the founder of the AF, significantly influenced Italian far-right thinkers through his ideas of integral nationalism, which resonated with Italian intellectuals seeking a unified nationalist ideology.[20] Maurras advocated a hierarchical, elite-driven society—principles that found alignment with Italian fascist ideologies. Italian philosopher Giovanni Gentile,[21] known as the “philosopher of fascism” under Mussolini, drew inspiration from European nationalist movements, including the AF. Although Gentile and Mussolini emphasized a fascist state over a monarchy, both shared Maurras’ vision of a centralized national authority.

In the interwar years, the AF regarded Mussolini’s rise as a model of national pride restored through authoritarianism. From Fascism’s early days, the AF supported not only its goals but also its methods,[22] with Maurras himself highlighting commonalities between his views and Mussolini’s.[23] Maurras saw Franco-Italian collaboration as a way to protect “Latin civilization” against the economic and cultural dominance of Anglo-Saxon countries and Germany. This vision for a “Latin Union” was developed further in 1929 in his Promenade italienne, where he looked at Italy’s Fascist regime as an opportunity to achieve this Franco-Italian alliance.[24]

The cross-border intellectual exchange did not stop there. Influenced by Maurras, Robert Brasillach—a writer for the AF and editor of the anti-Semitic magazine Je Suis Partout—became a notable figure in the Italian far right. Italian thinkers, especially Adriano Romualdi (son of MSI leader Pino Romualdi) and MSI leader Giorgio Almirante,[25] promoted Brasillach’s work. Romualdi translated Brasillach’s Letter to a Soldier of the Class of ’60 into Italian in 1964,[26] Italian far-right publications like Ordine Nuovo,[27] Noi Europa,[28] and L’Italiano[29] widely praised and disseminated Brasillach’s work throughout the 1970s. Furthermore, Il Secolo d’Italia, the MSI’s official newspaper, dedicated significant space to Brasillach, with Romualdi praising him in a full-page article in May 1964.[30] According to historian Pauline Picco, Ordine Nuovo, L’Italiano, and Il Secolo d’Italia contributed to establishing French writers like Brasillach as intellectual icons for the Italian far right.[31] Brasillach, an open supporter of fascism after the AF-led uprising of February 6, 1934, was executed as a Nazi collaborator on February 6, 1945; his brother-in-law, Maurice Bardèche, played an important role in the activities of the French Right in the post-war period.

Some former AF members, due to ideological differences, became closer to Italy. Two examples include Georges Valois and the PPF (French Popular Party): An AF member since 1906, Valois visited Italy in 1924 with Bernard de Vesins,[32] president of the AF league, to study Fascist methods firsthand. The delegation met key figures such as Curzio Malaparte and Francesco Coppola,[33] and eventually Mussolini himself.[34] In 1925, Valois left the AF to found Le Faisceau, France’s first fascist party, bringing along some AF members. Members of Le Faisceau included Marcel Bucard, who later formed the pro-collaborationist Francist Party, and Hubert Lagardelle, later Vichy’s labor minister. In 1926, Valois returned to Italy, meeting Margherita Sarfatti (Mussolini’s biographer and mistress), her brother Arnaldo, and Roberto Farinacci.[35]

Founded by Jacques Doriot in June 1936, the PPF attracted many former AF members, including Abel Bonnard, who became Vichy’s education minister after 1940. In 1937, Doriot positioned himself as France’s leading anti-communist, creating a “Front of Liberty” to counter the Popular Front and French Communist Party, with the AF providing unofficial support. The PPF received significant financial backing from Italy[36]; Mussolini’s Foreign Minister Galeazzo Ciano recorded in his diary a September 1937 payment of 300,000 francs to the PPF’s Victor Arrighi, head of its Algiers branch, to promote Italian interests within the party.[37]

Action Française Today: An Ideological Training Ground

Today, the AF boasts over a thousand members—it claims 3,000—making it the largest group on the right of the Rassemblement National. Maurras in his time had theorized four “confederate states” representing those he designated as enemies from within: the Jews, the Freemasons, the Protestants and the “metèques.” Today, however, the Muslim corresponds in this spirit to two of these “enemies” since he has replaced the Protestant as the religious enemy from within. In its current magazine—called L’action Française 2000 until 2019 and then Bien Commun—the AF still advocates the abolition of the republic and the return of the king, as well as the closure of borders, assimilation of so-called immigrant populations, and rejection of mass immigration.

From the outset, the AF has been referred to as a “movement” rather than a “party,” preferring to work in the shadows, out of the public eye—which has not prevented it from including MPs and even future ministers in its ranks. Its role is ideological and ‘cultural,’ concealing its extreme—and sometimes violent—intentions beneath the deceptive softness of ‘cultural’ propaganda. The AF provides the radical right and extreme right with an ideological framework—integral nationalism—and trains militants to spread the Maurrassian word outside AF circles.

There are three main training programs within the AF: the first is the “Cercles de formation,” which is reserved for its militants, while the second is the “Cercle de Flore,” named after the cafe where the leading antisemites of the AF met during their early days, which takes the form of conferences open to the public. The former evokes themes dear to the royalist roots of the AF, like the monarchy and the teachings of Maurras, and is seen as a pretext for networking and socializing among AF members. The latter responds to a different logic and attracts an audience of sympathizers that come to listen to a keynote speaker, often from outside the organization, as recently with Alain de Benoist[38] and Renaud Camus.[39] Thus, one aim of the Cercle de Flore is to expand the AF network beyond its militant base and into other right-wing and far-right circles. In 2013, for example, the AF invited Alain Soral to speak at one of their events, and in return an AF leader spoke at a conference organized by Égalité & Réconciliation, Soral’s movement, a few weeks later.[40]

A third training program is the Maxime Real del Sarte summer camp, named for lthe royalist sculptor who founded and led the violent Camelot du roi in the 1930s, through which passed a number of people who went on to enter politics, for example, Philippe de Villiers.

As a result, a number of young people have joined the radical movement, as well as others who have opted for more mainstream careers. Examples of the former are, at present, Thaïs d’Escuffon, ex-Génération Identitaire, now with Reconquête!; Alice Cordier, with Collectif Némésis; and Marc de Cacqueray-Valménier, leader of Zouaves Paris, then the GUD. The latter include those like Charlotte d’Ornellas, a regular on CNews and journalist at Valeurs Actuelles, and Journal Du Dimanche in the wake of Geoffroy Lejeune’s takeover.

In the academic world, Olivier Dard of the University of Lorraine and now Paris IV, and Bernard Lugan (who headed the AF’s security service in 1968) of Lyon III. Today, Lugan is one of the most popular figures of the extreme right on the Internet. Dard and Lugan remain close friends of the movement, where they regularly run “Cercles de formation” (training circles), Lugan being a regular guest at the AF summer camp. These long-standing relationships give young militants the impression that the AF is both a school and a network, guaranteeing social and professional success for those who commit themselves to it.

The AF can serve as a training ground for leaders, who can then go on to join the Rassemblement National (RN), Reconquête! or even more conservative parties. The case of Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin springs to mind here. “Darmanin reviens, the AF en besoin” (“Darmanin, come back, the AF needs you”), chanted AF militants in the streets of Paris on May 14, 2023, teasing Darmanin about his supposed passage through their ranks. It is a persistent rumor, regularly alluded to by the AF, but never fully confirmed or denied. One thing is certain: Gérald Darmanin has indeed written for a well-known AF-linked magazine, called Politique magazine,[41] and Christian Vanneste, the political godfather of Darmanin, was an active member of the movement.[42]

The Convergence of Action Française and Groupe Union Défense

Following the examination of the four generations of the GUD in Part 1 of this series, and then the exploration of the GUD’s connections with the Italian far right in Part 2, this third paper aims to investigate the GUD’s links to the AF and the Catholic far-right networks associated with it.

Academia Christiana: The Ideological Bridge

Academia Christiana was created in 2013 in the aftermath of the Manif pour Tous, a series of rallies organized by the Catholic far right to oppose a law on same-sex marriage. The goal of the AC, according to its website and flyers, is to “train the leaders of a reconquest of civilization.” We can therefore understand the role of the AC in the far-right galaxy as a training school, alongside others like Marion Maréchal’s ISSEP and Nouvelle Droite’s Illiade Institute. The AC provides ideological training through annual summer institutes and colloquiums.

Academia Christiana is sponsored by the Fraternité sacerdotale Saint-Pierre (FSSP), which represents a particular current of traditionalist Catholicism founded on July 18, 1988, one that is explicitly open to identitarian far-right ideology. Unlike the SSPX, which remains in a complex relationship with Rome, the FSSP enjoys canonical recognition from the Vatican while maintaining a hardline traditionalist stance. This ideological orientation is best summarized by one of its priests, Abbé de Nedde, who has openly stated that Catholicism and identitarianism can coexist[43], thus legitimizing the synthesis of religious traditionalism and ethnocentric nationalism within far-right circles. The FSSP is therefore fully aligned with Academia Christiana, whose officially stated goal, as reflected in its slogan, is to train a new generation of far-right militants who are “Catholic and rooted (“catholiques et enracinés”).

Other notable figures associated with the Priestly Fraternity of St. Peter (FSSP) include Allan Lopes dos Santos. In 2014, dos Santos launched a YouTube channel and blog called Terça Livre (Free Tuesday). He is currently a fugitive from Brazilian justice and has sought refuge in the United States. Brazilian authorities have accused him of advocating for a military takeover of the country and the dissolution of the Supreme Court.[44]

Another former FSSP figure is Father Chad Ripperger, founder of the traditional Catholic Society of the Most Sorrowful Mother (the Doloran Fathers), a community dedicated to the ministry of exorcism. On November 16, 2024, Ripperger gave a personal blessing to political commentator Jack Posobiec and his wife at Mar-a-Lago[45]. Following this event, Posobiec allegedly stated: “I certainly want to get him back to the White House, if and when he’s able to come in, because I know there’s some exorcism that needs to go on there.”[46]

FSSP was founded by former members of the Fraternité Saint-Pie X/Society of St. Pius X (SSPX). To understand what the SSPX is, we first need to understand why it was created and what it stands against.

The Second Vatican Ecumenical Council, commonly known as Vatican II, took place from 1962 to 1965. It is generally regarded as one of the most significant events in the history of Catholicism in the 20th century. The council acknowledged the growing secularization of societies and sought to adapt parts of the Catholic religion to that secularization to keep its followers within the Church. Those changes include a redesign of the liturgy (the way worship is celebrated, notably marginalizing the Tridentine mass where the priest is talking in Latin and turning his back to the congregation), while religious freedom in civil society was recognized by the Vatican and the Church broke with hostility toward other religions.

Some priests rejected the decisions of the Second Vatican Council because they believed these contradicted Pope Pius X’s condemnation of modernism. This opposition led to the creation of the SSPX in Switzerland in 1970 by Marcel Lefebvre, who chose to name the society after the anti-modernist pope. Lefebvre refused to accept the reforms of Vatican II and insisted on ordaining clergy within his dissident society, prompting the Pope to revoke his authorization to ordain priests and administer the sacraments. Despite this, Lefebvre went ahead and ordained additional priests at the seminary in Écône in 1988 — a ceremony attended by Prince Sixtus Henry of Bourbon-Parma, a Carlist claimant to the Spanish throne and a figure close to the French and international far-right[47]. As a result, Lefebvre was excommunicated by the Vatican.

Lefebvre was a disciple and admirer of Henri Le Floch, rector of the French Seminary in Rome and an associate of the AF. When the AF newspaper and Maurras were condemned by Pope Pius X in 1926, Le Floch was forced to resign by the French government because of his closeness to the AF.

Lefebvre was deeply affected by the condemnation of the AF, in which he saw the struggle for the Christian order that he himself desired. In 1974, he declared: “[The AF] was a movement of reaction against the disorder that Freemasonry was bringing to the country, to France: a healthy, definitive reaction, a return to order, to discipline, a return to morality, to Christian morality.”[48] Although Lefebvre claims to have never read Maurras or to have been a member of the AF, he does quote Maurras three times in one of his works.[49]

Maurrassians believe that when the restoration of the monarchy takes place, the Church will regain its privileged status like in the ancien régime and the clergy once again emerges the first order of the kingdom. For Catholics, the AF was the providential instrument for France’s return to monarchy and its Christian origins. In Rome, at least until the death of Pius X, the AF enjoyed serious support.[50]

The AF and the SSPX also used to share unwavering support for the Vichy government and collaboration with the Germans. While Maurras was special advisor to Pétain during World War II, in the 1980s the SSPX hid Paul Touvier, who had been sentenced to death in 1946 for crimes committed during World War II. Touvier was found by the police in 1989 at the Prieuré St. François, run by members of the SSPX, and convicted of complicity in crimes against humanity for the many he committed as head of the Lyon Milice.

The SSPX exists to this day but it is not recognized by the Vatican, which has given it the freedom to show its political preferences without embarrassment, notably openly supporting fascist dictators (Argentina’s Videla, Spain’s Franco, Portugal’s Salazar). In France, this is reflected in closeness to the far right and especially Jean-Marie Le Pen.

Some splinter groups were later formed to try and make up with the Vatican. All three were founded by SSPX members, maintain connections with it, and act as legal and recognized offshoots: The first is the FSSP, established in 1988, which sponsors the AC and within which the Dijon[51] and Lyon[52] chapters are close to the AF.

The second is the Institut du Bon-Pasteur, set up in 2006 by Father Philippe Laguérie after he was expelled from the SSPX for insubordination. Laguérie is known for his proximity with the Le Pen family, notably defending Jean-Marie Le Pen’s Holocaust denial statements in 1992[53] and performing the religious wedding of Jean-Marie and Jany Le Pen at their home in Rueil-Malmaison in 2021.[54] He also held a mass at the funeral of aforementioned war criminal Paul Touvier in 1996.[55]

Father Matthieu Raffray, assistant to the general manager of the Bon Pasteur, attends the AC summer institutes every year on behalf of Bon Pasteur. He is known for his Twitter (now X) hashtag of “bagarre bagarre prière” (“fight fight pray”) and for teaching young boys to box and shoot guns at his own summer camps.[56]

The third is the Fraternité Saint-Vincent-Ferrier, which was created in 1979 by Father Louis-Marie (born Olivier) de Blignières, born in Spain in 1949, who comes from a bourgeois family with many links to the far right and Catholic traditionalism. His father, Hervé, was chief of staff for the OAS, and his brother Hugues was editor-in-chief of the far-right magazine Présent in the 1980s. Father Louis-Marie de Blignières also attends the AC’s annual summer institutes.

The AC is deeply rooted in the French far right and linked to the most radical faction of the AF: the splinter group created in 2018 by Elie Hatem called “Amitié et Action Française.”[57] At the end of 2018, the AF split into the Centre royaliste d’AF (CRAF), commonly regarded as the main representative of the AF, and the newly founded Amitié et Action Française. At the root of the split was the banning of Elie Hatem by the CRAF.

Hatem was a regular speaker for the CRAF in the far-right media and at public meetings. Although he was not officially a member of the CRAF, he nevertheless drafted its legal statutes and was a regular contributor to its journal. His banishment was triggered by a financial dispute between the CRAF and Marie-Gabrielle Pujo, daughter of Maurice Pujo, cofounder of the AF movement in 1898 with Charles Maurras and founder of its paramilitary wing, Camelots du Roi. Pujo is the owner of Palais Royal Impress Editions Publicite (PRIEP), a printing company that used to publish L’action Française 2000, the AF newspaper after World War II. After unsuccessfully claiming 20,000 euros in unpaid invoices from the CRAF through its lawyer, Elie Hatem, PRIEP went into receivership in January 2018.

Since then, the CRAF has launched a new newspaper, called le Bien commun, but without Elie Hatem. Hatem has gone his own way with his Amitié et Action Française, still counting on the support of the Pujo family and other illustrious members of the AF, including Michel Fromentoux, editor of the now-defunct L’action Française 2000.

Today, Amitié et Action Française is an active member of the AC and remains close to far-right Catholic circles. On April 21, 2018, Hatem and his new group organized an homage to Maurras, which was attended by Abbé de Tanoüarn, cofounder of the Institut Bon Pasteur, Alain Escada, former chairman of Civitas, an offshoot of SSPX, Jean-Marie Le Pen, founder of the Front National, and Prince Sixtus Henry of Bourbon-Parma.[58]

The AC’s proximity to the French far right is further reflected in the pedigrees of its three cofounders. The first is Julien Langella: A member of AF from 2006 to 2008, he went on to create a chapter of Jeunesse Identitaire (the Bloc Identitaire youth section) in Aix-en-Provence, named “Recounquista” in 2008. Langella cofounded Génération Identitaire in 2012, which was shut down by government decree on March 2021. In 2013, Langella became cofounded the AC, where he served as vice-president. Since then, he assisted a Front National mayor in 2014.[59]

The second is Arno Guibert (aka Arnaud Danjou), the AC spokesman. He was briefly an AF member in 2016, before becoming a member of Alvarium,[60] a national-revolutionary far-right group close to the GUD. Alvarium, including its leader Jean Eudes Gannat, was close to the AC, mostly made up of the logistics team from the AC summer institutes.[61] When Alvarium was dissolved in November 2021, most of its members reorganized within the AC.

This closeness between Gannat, the AF and the AC is still visible today, for example, at the symposium organized by the AF on June 8, 2024, which included as speakers Gannat, now president of the Chouan movement, successor to Alvarium, Victor Aubert, president of the AC, and Guillaume de Salvandy, an AF executive.[62] Guibert was also briefly managing director of Le Marayeur in 2018—a restaurant in Paris that organizes far-right conferences and is owned by Olivier Courtois, who sits on the national council of Reconquête! (Zemmour’s party), and Philippe Cuignache, also of Reconquête!, and a former GUD leader in the 1970s.[63] Previously, he worked as managing director or the Nouvelle Droite bookshop Nouvelle Librairie until 2019.

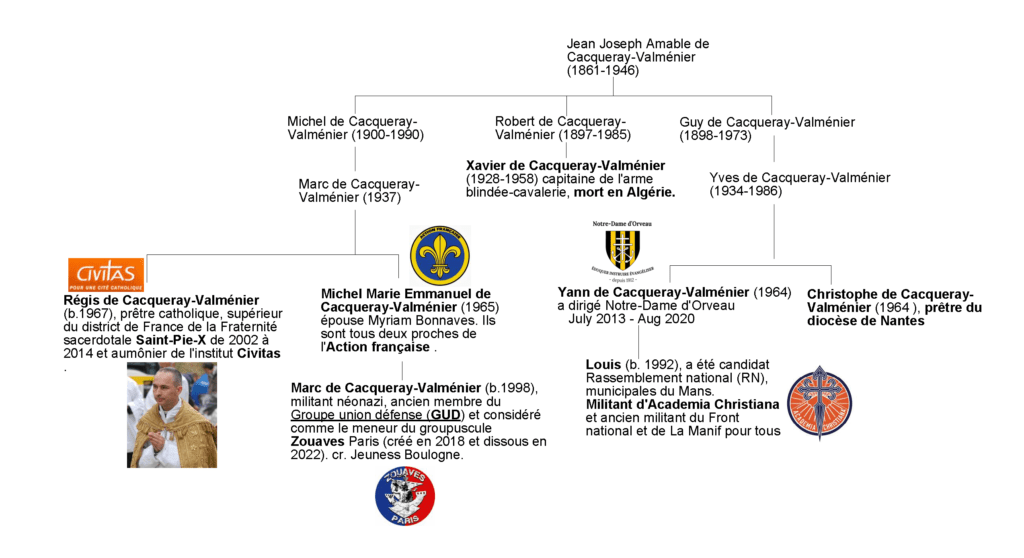

family tree of the De Cacqueray-Valmenier family

The third and final cofounder of the AC is Victor Aubert, who attended the catholic far-right school Notre-Dame d’Orveau in his youth with Alvarium cofounder Gannat. Notre-Dame d’Orveau was headed by Yann de Cacqueray de Valménier, cousin of Régis de Cacqueray de Valménier, former head of the French branch of SSPX (see the family tree chart above). After cofounding the AC in 2013, Aubert has since 2015 taught French and philosophy at Institut Croix-des-Vents in Sées, a school run by the FSSP with no recognition by the French state. Note that Aubert was seen marching alongside GUD members and giving a Nazi salute at the Manif pour Tous on October 16, 2016,[64] and he gave a speech at an AF rally on January 20, 2018, honoring the memory of Louis XVI.[65] More recently, in 2022, he created Apollon Communication, a PR firm that provides services for the FSSP, which again illustrates the bridges and overlaps that exist between these different groups. The AC links two movements that never used to mix: the Catholic-royalist movement of the AF and the national-revolutionary movement led by the GUD, which includes a myriad of other groups, like Alvarium, in its orbit.

A poster for the third youth symposium organized by the AF, slated for Saturday, June 8, 2024. the round table “quel combat pour demain” features the following speakers: Jean-Eudes Gannat from Mouvement Chouan, Victor Aubert from the AC and Guillaume de Salvandy from the AF.

Source: Action Française – Paris Facebook

The Fourth Generation of Groupe Union Défense and Hybridization.

Although the AF claims to give intellectual training to its militants, the desire for radicalism and action has always permeated the movement’s youth. This is the role of the Camelots du Roi, the AF movement’s protection service created in 1908. Officially disbanded by the Interior Ministry in 1936, this section of the AF, which was intended for demonstrations of force, nevertheless lives on, at least symbolically, today, having got a violent reputation in the press.

In Aix, for example, in 2016 the AF organized an incursion into a PCF office, attacking communist militants with truncheons.[66] One of the members of the Aix section, Paul-Antoine Schmitt, was convicted of “racially motivated violence in a meeting.”[67] At the time, Schmitt was in charge of the local section of Génération Zemmour (the youth wing of Reconquête!).[68] Generally speaking, most AF activists campaigned for Eric Zemmour in 2022.[69] At Reconquête!’s launch meeting in December 2021, several anti-racist activists were violently assaulted by far-right thugs, and the AF was even seen hawking its newspaper, Le Bien Commun.[70]

The AF has gone through several phases of violent activism, having been close to Troisième Voie in the 1980s, followed by the GUD today. Recently, two local AF chapters split off to form autonomous groups that are part of the decentralized GUD network: In 2018, the Aix en Provence and Marseille chapters split and united to form Tenesoun; in January 2023, the Rennes chapter of the AF broke away to form L’Oriflamme.

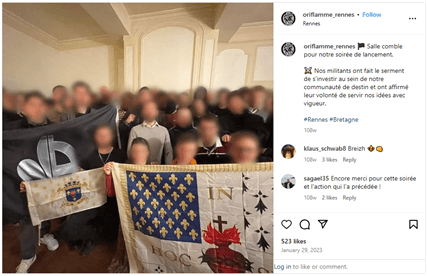

The split between the AF and its Rennes branch was made official on January 3, 2023. A few days later, a photo was posted online by L’Oriflamme, showing 16 militants posing behind a flag emblazoned with a half-lily, the royal emblem of the AF, joined by a Celtic half-cross, the symbol of French neofascists and the GUD. Since moving away from the AF and toward the GUD, L’Oriflamme has kept the same leader, Marc Visada.

The story of L’Oriflamme and its logo, which brings together the iconography of both groups, is exemplary of the creation of hybrid groups. The new allegiance to the GUD was made official in March 2023, when L’Oriflamme was invited to take part in a colloquium organized by Lyon Populaire—another group affiliated with the GUD—alongside the GUD and Alvarium.

The emblem on the black flag on the left indicates the linkage of the AF’s fleur-de-lis and the pagan Celtic cross of GUD.

Source: screenshot of @oriflamme_rennes Instagram post

Other local AF chapters have since followed suit, breaking away from the AF and founding independent groupuscules now linked to the GUD: notably, Remes Patriam in Reims in December 2022 and Meduana Noctua in Laval in January 2023.

This phenomenon of hybridization between the AF and the GUD also concerns the leadership of the movement itself. Indeed, the leaders of the Paris section of the AF are very close to those of the Paris GUD, the fourth generation of the GUD set up by Marc de Cacqueray de Valmenier.

Marc de Cacqueray de Valmenier (MCV), leader of the now-defunct Paris GUD, is no stranger to the far-right networks we have presented so far: his parents were both close to the AF; his uncle, Régis de Cacqueray de Valmenier, was a representative of the SSPX in France and its offshoot far-right group Civitas; finally, a distant relative, Louis de Cacqueray de Valmenier, was a Rassemblement National candidate in municipal elections and a member of theAC.

In 2015–2016, the GUD and the AF collaborated regularly in Paris, also meeting frequently at Le Crabe-tambour, a room rented by the GUD and turned into its own bar. In 2016, at the age of 17, MCV was the young leader of the high school section of the Paris AF. He sympathized with GUD militants to such an extent that, in June 2016, he declared himself a member of both the AF and GUD. In October 2016, faced with these contradictory commitments by the AF leadership, he left the AF and fully committed to the GUD. When the GUD third generation was renamed Bastion Social in 2017, the GUD would rally to itself not only local groupuscules but also large parts of the AF, such as the Aix and Marseille chapters mentioned above. MCV then founded les Zouaves—which became the de facto Paris branch of Bastion Social—with two other Paris AF members, Aloys Vojinovic and Louis David. This motley crew brought together elements of the three main far-right groups at the time: the AF, GUD and Identitarians. The rest is history: The Zouaves were dissolved by government decree in January 2022, and MCV reactivated the GUD—thereby launching its fourth generation—in November 2022,[71] permitting thereafter the Paris GUD and the French section of the AF to continue their close collaboration.

Conclusion

The hybridization of the GUD and AF, facilitated by networks like the AC, demonstrates how different strands of the far right are converging into a more cohesive and adaptive movement. Historically, the GUD represented militant nationalist activism, while the AF was rooted in monarchist, Catholic traditionalism. Their modern collaboration, however, signals a shift toward a more interconnected far right, where militancy and intellectual conservatism coalesce. This enables both movements to broaden their influence and appeal.

The Catholic networks explored in this paper, particularly the AC, reveal how religious ideology strengthens these ties, adding moral legitimacy to the militant activism of the GUD. This coalition of intellectual tradition and grassroots militancy creates a more resilient far-right structure capable of navigating contemporary political landscapes. As both the GUD and AF face pressures from within and without, their hybridization forms a buffer against the challenges and ensures adaptability.

Even though the Paris GUD was officially dissolved in June 2024, the decentralized and fragmented nature of its fourth generation marks a key shift in how these movements operate. The dissolution of the Paris GUD is unlikely to severely impact the far right as a whole, given that this central body primarily acted as a mouthpiece, with much of its actual activity occurring across independent, loosely connected groups. This decentralized model, with a particularly focus on social media, allows the GUD to remain influential despite formal bans and even dissolutions. The organization’s survival depends less on a central authority and more on its ability to adapt through local chapters and virtual networks, to make it resilient against government attempts to curb its influence.

Moreover, the dissolution of the AC, announced in December 2023, has yet to fully shut down the organization. The ideological and militant infrastructure established by these groups continues to operate and grow, underscoring the far right’s capacity to reform and adapt to external pressures.

In conclusion, this paper emphasizes the importance of these evolving far-right networks. The ongoing cooperation between the GUD and AF, bolstered by Catholic traditionalist ties, reflects a strategic hybridization that enables these movements to expand their influence. The decentralized, fragmented nature of the GUD’s fourth generation ensures its survival, despite the organization’s formal dissolution, by shifting toward a more flexible and resilient structure. This blend of intellectual discourse, religious nationalism, and militant activism ensures that the far right in France will remain a potent force as it leverages its decentralized networks to navigate challenges and continue appealing to a broader audience.

[1] Brut, “Gérald Darmanin répond à Brut,” YouTube, December 11, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gsQVfBtUuxs&ab_channel=Brut.

[2] Eric Zemmour, X post, December 10, 2023, https://x.com/ZemmourEric/status/1733925652116422924

[3] “Darmanin veut la dissolution d’Academia Christiana, mouvement catholique traditionaliste d’extrême droite,” Le Parisien, December 11, 2023, https://www.leparisien.fr/faits-divers/darmanin-veut-la-dissolution-dacademia-christiana-mouvement-catholique-traditionaliste-dextreme-droite-11-12-2023-ZFOCSC4NH5CV3GNN2GDYATYQGE.php?ts=1734613668225.

[4] “Plongée au sein d’Academia Christiana, mouvement catholique et nationaliste placé dans le radar des services de renseignement”, France Info, February 6, 2022, https://www.francetvinfo.fr/societe/religion/enquete-france-2-plongee-au-sein-d-academia-christiana-mouvement-catholique-et-nationaliste-place-dans-le-radar-des-services-de-renseignement_4965042.html

[5] Emilie Jehanno, « Qu’y a-t-il derrière Academia Christiana, le mouvement catholique traditionaliste que veut dissoudre Darmanin ? », 20 Minutes, December 12, 2023, https://www.20minutes.fr/politique/4066364-20231212-derriere-academia-christiana-mouvement-catholique-traditionaliste-veut-dissoudre-darmanin

[6] After its dissolution, Génération Identitaire continues to exist via its Lille branch called Citadelle, founded in October 2013 and dissolved in February 2024. Génération Identitaires alumni also created two new structures: Les Remparts, founded in September 2021 and dissolved in June 2024, and the Association de Soutiens aux Lanceurs d’Alerte (ASLA) created in May 2021. For more information on ASLA: Daphné Deschamps, « L’Asla, l’association de défense des identitaires qui veut faire la peau à SOS Méditerranée », StreetPress, October 26, 2023, https://www.streetpress.com/sujet/1698230796-asla-association-defense-identitaires-sos-mediterannee

[7] Stéphane François, Un monde conçu en choc des civilisations. Géopolitique des extrêmes droites : Logiques identitaires et monde multipolaire (Le Cavalier Bleu, 2022), 151–57, https://shs.cairn.info/geopolitique-des-extremes-droites–9791031805030-page-151?lang=fr.

[8] Archives de la préfecture de police de Paris (henceforth APP), BA 1341, RG report, June 21, 1899.

[9] Henri Vaugeois, “Réaction, d’abord,” L’Action française, fortnightly review, August 1, 1899.

[10] Laurent Joly, “Les débuts de l’Action française (1899-1914) ou l’élaboration d’un nationalisme antisémite,” Revue historique 639 (July 2006): 695–717.

[11] Joly, Revue historique, 712.

[12] Thomas Snégaroff, “Comment Jeanne d’Arc a été privatisée par le Front national (1985-2015),” France Info, April 25, 2015, https://www.francetvinfo.fr/replay-radio/histoires-d-info/comment-jeanne-d-arc-a-ete-privatisee-par-le-front-national-1985-2015_1776401.html.

[13] Joly, Revue historique, 703.

[14] Joly, Revue historique, 707–708.

[15] Joly, Revue historique, 716.

[16] Laurent Joly, “Tradition nationale et ‘emprunts doctrinaux’ dans l’antisémitisme de Vichy,” in Michele Battini and Marie-Anne Matard-Bonucci, eds., Antisemitismi a confronto: Francia e Italia. Ideologie, retoriche, politiche (Pisa: Edizioni Plus/Pisa University Press, 2010), 139–154.

[17] Gisèle Sapiro, “Stratégies internationales de polémistes français d’extrême droite: perspective socio-historique,” Revue des sciences humaines 351 (2023): 17–34.

[18] With the exception of those who have rendered ‘exceptional service’ to the country and, in the case of junior positions, veterans and their families.

[19] Karine Varley, “Defending Sovereignty without Collaboration: Vichy and the Italian Fascist Threats of 1940–1942,” French History 33, no. 3 (September 2019): 422–443, https://doi.org/10.1093/fh/crz064

[20] Zeev Sternhell, Neither Right nor Left: Fascist Ideology in France (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995).

[21] Emilio Gentile, The Origins of Fascist Ideology, 1918–1925 (New York: Enigma Books, 2005).

[22] Pierre Milza, Le fascisme italien et la presse française: 1920–1940 (Brussels: Complexe, 1987), 89.

[23] L’Action française, July 18, 1923.

[24] Catherine Valenti, “Une Promenade italienne de Charles Maurras (1929): Le couple franco-italien au cœur du projet d’« Union latine »,” Anabases 35 (2022), http://journals.openedition.org/anabases/13388.

[25] Giorgio Almirante, Robert Brasillach (Rome: Ciarrapico Editore, 1979).

[26] Adriano Romualdi, “Robert Brasillach,” in Robert Brasillach, Lettera ad un soldato della classe 40 (Edizione Caravelle, 1964).

[27] Iginus, “Lettera a un soldato della classe 40,” Ordine Nuovo XI, no. 1–2 (January–February 1965): 87.

[28] Pino Tosa, “Omaggio a Brasillach,” Noi Europa (May 1968): 34.

[29] Pauline Picco, “Chapitre VII. Des passerelles idéologiques pour penser un monde commun,” in Liaisons dangereuses (Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2016), https://doi.org/10.4000/books.pur.46757.

[30] Adriano Romualdi, “Brasillach,” Il Secolo d’Italia, May 9, 1964, 8.

[31] Liaisons dangereuses, op. cit.

[32] Olivier Dard, “La nébuleuse maurrassienne et la marche sur Rome,” Cahiers de la Méditerranée 107 (2023), https://doi.org/10.4000/11x4u.

[33] Georges Valois, L’homme contre l’argent. Souvenirs de dix ans, 1918-1928, ed. Olivier Dard (Villeneuve d’Ascq: Presses Universitaires du Septentrion, 2012), 105–109.

[34] Christophe Poupault, À l’ombre des faisceaux. Les voyageurs français dans l’Italie des chemises noires (1922-1943) (Rome: École française de Rome, 2014), 204.

[35] Georges Valois, L’homme contre l’argent, ed. Olivier Dard (Villeneuve d’Ascq: Presses Universitaires du Septentrion, 2012), 267–269, https://doi.org/10.4000/books.septentrion.71683.

[36] Serge Berstein and Pierre Milza, Dictionnaire historique des fascismes et du nazisme (Brussels: Complexe, 2010), 153–156.

[37] G. Ciano, Journal 1937-1938 (Paris, 1949), 23.

[38] Cercle de Flore, Facebook post, February 25, 2023, https://www.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=3352225345018551&id=1506614376246333&m_entstream_source=timeline&_rdr.

[39] Cercle de Flore, Facebook post, https://www.facebook.com/events/cercle-de-flore/renaud-camus-petit-et-grand-remplacements/2665856796866069/.

[40] Robin d’Angelo, “Une scission et l’Action française ne sait plus comment elle s’appelle,” Libération, March 18, 2019, https://www.liberation.fr/france/2019/03/18/une-scission-et-l-action-francaise-ne-sait-plus-comment-elle-s-appelle_1715996/?redirected=1.

[41] Nadia Sweeny, “Gérald Darmanin a-t-il milité à l’Action française ?,” Politis, February 5, 2021, https://www.politis.fr/articles/2021/02/gerald-darmanin-a-t-il-milite-a-laction-francaise-42806/.

[42] Maxime Macé and Pierre Plottu, “L’Action française, école des cadres réactionnaires,” StreetPress, June 29, 2023, https://www.streetpress.com/sujet/1687965898-action-francaise-ecole-cadres-reactionnaires-darmanin-ministres.

[43] Academia Christiana. (2017, June 26). Catholicisme et identité – Abbé de Nedde [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-c23aNkWk9o.

[44] Terrence McCoy, “Brazilian Judge Suspends Rumble, Host of Trump’s Truth Social Platform,” Washington Post, February 22, 2025, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2025/02/22/brazilian-judge-suspends-rumble-platform-owned-by-trump-ally/.

[45] Tanya Tay Posobiec (@realTanyaTay), “This morning @JackPosobiec and I were honored to receive a personal blessing from Fr @RippergerQuotes. The battle is not over bc this is a spiritual war 🙏🏻✝️,” X (formerly Twitter), November 16, 2024, 7:24 PM, https://x.com/realTanyaTay/status/1857852378348667121.

[46] Matt Gaspers (@MattGaspers), “This week, @JackPosobiec joined @rustyrockets and talked about his time with Fr. Chad Ripperger at Mar-a-Lago last Friday: ‘Elon was there, Trump was there.’ ‘I certainly want to get him back to the White House, if and when he’s able to come in, because I know there’s some exorcism that needs to go on there.’ @realDonaldTrump could always politely ask @WashArchbishop to grant Fr. Ripperger faculties (just sayin’),” X (formerly Twitter), November 23, 2024, 3:39 AM, https://x.com/MattGaspers/status/1857852378348667121.

[47] An event that attests to the international connections of Prince Sixtus Henry of Bourbon-Parma is his presence at the meeting organized by Konstantin Malofeev on May 31, 2014, in Vienna, celebrating the 200th anniversary of the Holy Alliance of Metternich, which had the implicit aim of recreating a large pro-Russian conservative international in Europe. The participants included, notably: the fascist philosopher Alexander Dugin, the controversial painter Ilia Glazounov, known for his large nationalist and anti-Semitic murals, Aymeric Chauprade, who was then a close advisor to Marine Le Pen, Marion Le Pen-Maréchal, Heinz-Christian Strache, leader of the far-right Austrian FPÖ party, his ally Johann Herzog, as well as far-right leaders from Bulgaria and Croatia.

Laruelle, Marlene. Le “soft power” russe en France: La para-diplomatie culturelle et d’affaires. January 8, 2018. Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs. https://cdn.carnegiecouncil.org/media/cceia/Le-soft-power-Russe-en-France_2_2023-04-10-045557_klrz.pdf?v=1671038458

“Réunion prorusse à Vienne de partis d’extrême droite européens.” AFP. Published June 4, 2014. Libération. https://www.liberation.fr/planete/2014/06/04/reunion-prorusse-a-vienne-de-partis-d-extreme-droite-europeens_1033208/?redirected=1

Zubrin, Robert. “The Wrong Right.” The National Review, June 24, 2014. https://www.nationalreview.com/2014/06/wrong-right-robert-zubrin/

[48] Bernard Tissier de Mallerais, Marcel Lefèbvre, une vie (Étampes: Clovis, 2002), 47, 60.

[49] Mgr Lefebvre, Ils l’ont découronné (1987), 13, 43, 113.

[50] Including: Cardinal Billot, former professor at the Gregorian University, Père Le Floch, superior of the French Seminary, Mgr Abel Gilbert, former bishop of Le Mans, Mgr Sabadel, alias Pie de Langogne, and Père Joseph Lemius. Jacques Prévotat, Les catholiques et l’Action française. Histoire d’une condamnation (Paris: Fayard, 2001), 176–179.

[51] “À la Fraternité Saint-Pierre de Dijon, des soutiens pas (toujours) très catholiques,” Radio Bip, July 12, 2021, https://radiobip.fr/site/blog/2021/07/12/a-la-fraternite-saint-pierre-de-dijon-des-soutiens-pas-toujours-tres-catholiques/.

[52] Paul Ganassali, “À Lyon, cathos tradi et militants identitaires tissent des liens,” Le Nouvel Obs, September 22, 2023, https://www.nouvelobs.com/societe/20230922.OBS78503/a-lyon-cathos-tradi-et-militants-identitaires-tissent-des-liens.html.

[53] Richard Bellet, “Ce que disent ceux qui l’ont quitté,” L’Événement du Jeudi, March 18–25, 1992, 47.

[54] On January 16, 2021, he religiously married Jean-Marie and Jany Le Pen at their home in Rueil-Malmaison.

[55] “Paul Touvier a été inhumé au cimetière communal de Fresnes,” Le Monde, July 27, 1996, https://www.lemonde.fr/archives/article/1996/07/27/paul-touvier-a-ete-inhume-au-cimetiere-communal-de-fresnes_3723396_1819218.html.

[56] “#bagarrebagarreprière: l’abbé Raffray, la Bible et le fusil,” La Horde, November 18, 2021, https://lahorde.info/bagarrebagarrepriere-l-abbe-Raffray-la-bible-et-le-fusil.

[57] Ronan Planchon, “Jean-Yves Camus: « L’influence de Civitas, une organisation connue pour son antisémitisme, reste faible »,” FigaroVox, August 9, 2023, https://www.lefigaro.fr/vox/societe/jean-yves-camus-l-influence-de-civitas-connue-pour-tenir-des-propos-antisemites-reste-faible-20230809.

[58] Pierre Olivier, “Hommage à Charles Maurras avec Yvan Benedetti – 21 avril – Avignon,” Jeune Nation, https://jeune-nation.com/nationalisme/natio-france/hommage-a-charles-maurras-avec-yvan-benedetti-21-avril-avignon.

[59] “Cogolin: un fan de Mussolini assure la com’ du maire FN,” La Horde, November 12, 2014, https://lahorde.info/cogolin-un-fan-de-mussolini-assure-la-com-du-maire-fn.

[60] Arthur Weil-Rabaud, “Le bar à huîtres préféré de l’extrême droite parisienne,” StreetPress, September 26, 2023, https://www.streetpress.com/sujet/1695652604-bar-huitres-prefere-extreme-droite-parisienne-conversano-zemmour.

[61] “L’université d’été 2022 d’Academia Christiana de retour en Anjou et en catimini,” Réseau Angevin Antifasciste, October 1, 2022, https://raaf.noblogs.org/post/2022/10/01/luniversite-dete-2022-dacademia-christiana-de-retour-en-anjou-et-en-catimini/.

[62] Action Française Paris, Facebook post, May 23, 2024, https://www.facebook.com/actionfrancaiseparis/photos/-colloque-de-la-jeunesse-%EF%B8%8F-table-ronde-quel-combat-pour-demain-avec-jean-eudes-g/788052466842879/?paipv=0&eav=AfY94pU8-mtmATWLj1vatK5nkgnhBkmSDU50SM4hzqDiWIfxfbIQjcAIpo9wV5kJWAE&_rdr.

[63] Arthur Weil-Rabaud, “Le bar à huîtres préféré de l’extrême droite parisienne,” StreetPress, September 26, 2023, https://www.streetpress.com/sujet/1695652604-bar-huitres-prefere-extreme-droite-parisienne-conversano-zemmour.

[64] “Qui sont les ‘personnalités’ qui appellent à soutenir Génération identitaire dans Valeurs actuelles ?,” La Horde, October 22, 2018, https://lahorde.info/qui-sont-les-personnalites-qui-appellent-a-soutenir-generation-identitaire-dans-valeurs-actuelles.

[65] Academia Christiana, Facebook post, January 27, 2018, https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=1598153883606386.

[66] Sabrina Guintini, “L’Action française toujours impunie à Aix,” La Marseillaise, June 11, 2016, https://www.lamarseillaise.fr/politique/l-action-francaise-toujours-impunie-a-aix-IFLM049427.

[67] Célestin Navarro, “Un militant de l’Action Française condamné pour une agression raciste à Aix-en-Provence,” France Bleu, March 2, 2023, https://www.francebleu.fr/infos/faits-divers-justice/un-militant-d-action-francaise-condamne-a-de-la-prison-pour-agression-raciste-a-aix-en-provence-7104028.

[68] Maxime Macé and Pierre Plottu, “Génération Zemmour éclaboussé par une affaire d’agression raciste,” Libération, March 6, 2023, https://www.liberation.fr/politique/generation-zemmour-eclabousse-par-une-affaire-dagression-raciste-20230306_CIQPTZKGTFBGVL243XWLJXVVQE/.

[69] Eloise Lebourg, “Action Française, son camp d’été en Auvergne!,” Media Coop, August 30, 2023, https://mediacoop.fr/30/08/2023/action-francaise-son-camp-dete-en-auvergne/.

[70] Tristan Berteloot and Nicolas Massol, “Eric Zemmour en meeting à Villepinte, un brun flippant,” Libération, December 5, 2021, https://www.liberation.fr/politique/elections/zemmour-a-villepinte-un-brun-flippant-20211205_WCZDOUPTMJC4NFOYXXZITGVRYM/.

[71] Pierre Plottu and Maxime Macé, “Des militants d’extrême droite réactivent le GUD à Paris,” Libération, November 7, 2022, https://www.liberation.fr/politique/des-militants-dextreme-droite-reactivent-le-gud-a-paris-20221107_JIFRX37RJJD2BABP2MLJ37R7YY/.